Most Americans agree that Congress is not functioning nearly as well as it should. Only about a third of us have a favorable view of Congress.

We also understand that an effective Congress is crucial to realizing the full promise of American self-government. The Framers established Congress’ central roles in Article One of the Constitution, reflecting their conviction that the legislative branch is even more crucial in representative government than the president (Article Two) and the courts (Article Three).

Congress is also where growing partisan rancor and dysfunction is often most visible. For example, research analyzing the more than 13 million roll call votes cast since the 1st Congress in 1789 reveals that partisan polarization is greater in the Congress today than at any previous time in our more than 230 years under the Constitution. In a system of government intentionally designed by the Founders to prevent any one party from imposing its will on everyone else, increasingly partisan approaches to lawmaking translate into a stalemate and an inability to address the crucial challenges of our day.

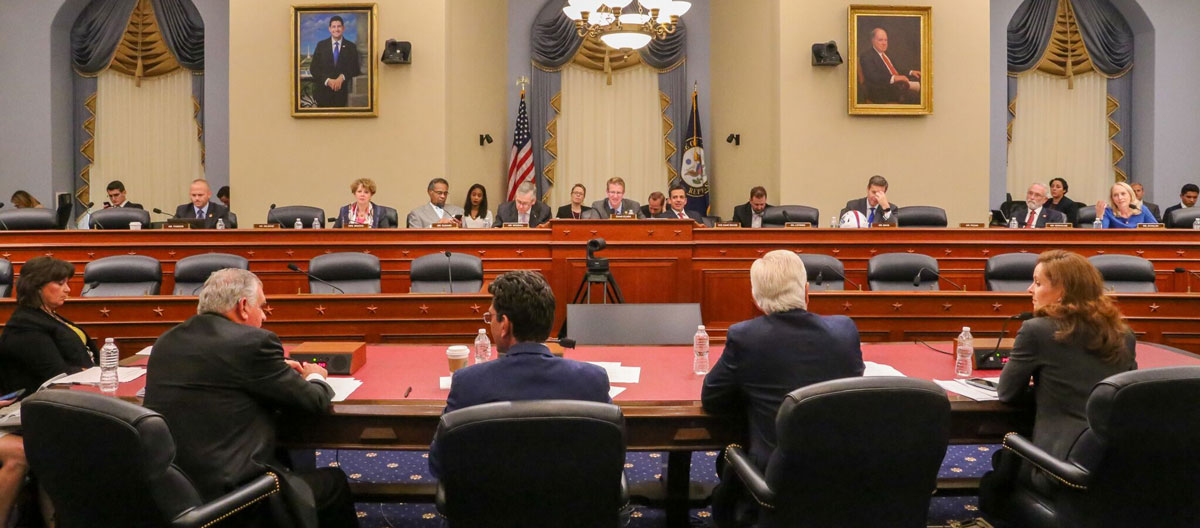

Can anything be done that could realistically make Congress more effective? Several serious efforts have suggested congressional reforms that would make a difference. Lead among these efforts has been the Select Committee on Modernization of the Congress. Established early in 2019, the Select Committee has been a rare bright spot of substantive, bipartisan problem-solving in Congress. Chairman Derek Kilmer (D-WA) and Co-Chairman Tom Graves (R-GA) have capably led a process that resulted in 97 specific recommendations. In an impressive feat of bipartisanship in our polarized day, each recommendation was unanimously supported by all six Democrats and all six Republicans on the Committee. Because it is a committee of the House of Representatives, the Select Committee recommendations focus on that chamber. Nevertheless, the reforms are also a model for what could be done in the Senate.

Reflecting how thorough and substantive the Select Committee has been, its Final Report describing the evidence and rationale for the 97 unanimous recommendations is 292 pages long. We’ve designed several features of this brief to make our coverage of their extensive work manageable. First, we have divided it into two main sections. The first section focuses on reforms aimed at fostering civility and bipartisanship. Because it is so central to the current dysfunction, as well as to the mission of the National Institute for Civil Discourse (NICD) and its CommonSense American program, these reforms get the fullest attention. The second section focuses on eight additional categories of Select Committee recommendations. In this second section we provide an overall description of each category as well as a few examples of specific recommendations.

The second feature aimed at making this brief manageable for you to review is that we’ve put our usual descriptions of the strongest arguments for and against a given proposal in a Pro/Con link. Because the Select Committee focused so successfully on identifying the most obvious, commonsense reforms wise enough to attract unanimous, bipartisan support among the six Democratic and six Republican committee members, there frequently is less of an argument against a given proposal than is usually the case in CommonSense American’s other briefs. There is, however, always an argument for and against. You can review those in the Pro/Con link.

To Download a PDF of the Final Report Click Here

Third, we provide links that will take you directly to the relevant part of the Select Committee’s Final Report, as well as links to other relevant sources. In many cases, our brief paraphrases the relevant section of the Final Report which you can easily go to yourself through the links.

While it would take a very long time to review all of the additional information contained in the links, we recommend that you chose to review the pro/con arguments and the relevant portions of the Select Committees Final Report for at least some of the recommendations. We suggest that you do that where you think it would be most helpful to formulating your own informed conclusion about whether to support or oppose them. Research indicates that if even a limited number within a large group like ours dives deeper into any one particular part of a big policy question, the overall result reflects the wisdom gained from the deeper information to a surprising degree.

FOSTERING BIPARTISANSHIP & CIVILITY

Congressional stalemate due to partisan contention doesn’t just limit Congress in fulfilling its Article One responsibilities. It also places increasing strain on the other branches. As the first of the three branches of government, the Founders charged Congress with a lead responsibility for policy making and significant oversight responsibilities. Because bitter partisan fighting has limited the ability of Congress to fulfill its crucial roles, the Executive and Judicial Branches have increasingly stepped into the breach, taking on roles for which they are ill-suited.

1.1 Committee Reforms

The Select Committee and the more than a dozen experts NICD convened agreed that congressional committees are an especially productive setting in which to establish stronger bipartisan relations. First, committees provide a smaller, more intimate, and manageable opportunity for relationship building. Second, good bipartisan relations among committee Members are especially important because committees are charged by the full body with developing good legislation on topics over which they have jurisdiction. Getting the policy right at the committee level can be the key to Congress passing legislation wise enough to attract bipartisan support.

1.1.1 Committes should hold bipartisan meetings outside of formal hearings

Members of committees rarely meet together outside of formal hearings. The partisan formats and formality of those hearings make it challenging to forge meaningful, effective relationships with Members of the other party. The Select Committee and NICD’s more than one dozen experts suggest that committee Members supplement the formal hearings with a few types of other gatherings aimed at fostering bipartisanship and civility. Of the 12 reforms that NICD developed, the two recommendations for committee meetings outside formal hearings received among the highest average ratings from our panel.

The reform receiving the second highest average rating of 3.75 (where a “3” means “promising” and a “4” means “very promising”) was holding committee retreats every two years, ideally at the beginning of each new Congress. This recommendation was also adopted by the Select Committee. Committees would meet every two years to determine the committee’s goals, how Members will treat each other in public and private, and how the committee will treat witnesses during hearings (see Chap 10, Recommendation 5).

The reform receiving the third highest average rating of 3.58 among NICD’s more than a dozen experts was that Members of congressional committees meet informally on a quarterly or monthly basis to focus on a general topic of mutual interest. The meetings could include talks and panels by experts. The topics need not be strictly related to legislative topics.

Recognizing the critical role that staff play, the Select Committee also suggested regular meetings for committee staff that would focus on bipartisan briefings and trainings to make hearings more productive and non-partisan (See Chap 2, Recommendation 4).

Finally, the Select Committee also suggested pre-hearing committee meetings at which Members and staff of both parties would set goals for the hearing, work to reduce surprise tactics, defuse partisanship, and coordinate witness questions for the purpose of having more productive and substantive hearings (see Chap 10, Recommendation 3).

PROS & CONS

The Case For: When committee Members and staff come to see each other as fellow human beings who share a commitment to our country’s success and have common personal interests, hopes and challenges, it becomes easier to treat each other with respect and civility. The improved relations, in turn, foster productive engagement of substantive differences in the service of sound decision making at the committee level, which is an especially productive and consequential level at which to do this.

The Case Against: Some argue that because their party simply has a better vision and ideas for the country than the other, working in bipartisan ways is of little use. If in the majority, the time and effort is better spent advancing the mandate the voters gave the party. If in the minority, better to focus on making one’s party the majority. Even if their own party committed to engaging the other side with greater consideration and respect, the other side will not return the favor, making attempts at bipartisanship futile. Interestingly, both sides make that claim about the other side.

1.1.2 Committees should experiment with alternative hearing formats

Typically, the seating at a committee hearing is classic “across the aisle” seating, with Republicans on one side and Democrats on the other. Time is typically allocated so that witnesses have five minutes to speak and then committee members each have five minutes to ask the witnesses questions. The Select Committee suggested that changing these formats could better foster bipartisan relations and provide better information to the committee (see Chap 10, Recommendation 1). For example, seating could alternate Republican and Democrat so that each Member has a Member from the other party on either side of them. Instead of five-minute blocks for individual Members, groups of Members could be given 30-minute blocks and coordinate their questions.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Alternating Republicans with Democrats in the seating provides better opportunities for Members to develop fuller, more constructive relationships with each other. The Select Committee itself frequently adopted that seating. The Committee Members agreed that this contributed to the strong bipartisan spirit that prevailed. The state legislature in Maine has adopted the same seating arrangement to good effect. Maine legislators report that it has fostered trust and cooperation across the partisan divide because they come to know each other as complete human beings rather than as the stereotype of an opposing political party. As they share with each other aspects of their lives beyond the legislature, from professional experiences to what their grandkids are doing, genuine respect grows. As one Maine legislator told NICD, “It’s easier to work across the aisle when there is no aisle.” Giving groups of Members larger time blocks in which they can coordinate questions, the Select Committee suggests, can reduce the amount of time used on political statements and increase the amount of time that produces substantive information.

The Case Against: Some argue that sitting together as a party is important for coordinating the party’s efforts to advance its agenda and block the other party’s. Some also make the argument that making the case for their party is an appropriate use of a Members five minutes to ask a witness a question.

1.1.3 Committees should hire bipartisan staff

Today, most House committees hire separate majority and minority administrative staff to do things like set up the hearing room, handle reports, and archive material. The Select Committee suggested that these staff instead be hired on a bipartisan basis, approved by both the Chair and Ranking Member, who is the most senior Member of the minority party on the committee (see Chap 10, Recommendation 2).

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Staff will know that they work for Members of both parties and approach their work accordingly. Bipartisan staff will have greater job security and tenure because their jobs are not dependent on which party is in the majority. The combined effect, the Select Committee suggests, would be to promote strong institutional knowledge, evidence-based policy making, and a less partisan oversight agenda. The Committee also suggests that this measure would save money by reducing staff overlap.

The Case Against: Some argue that it is important for their party to be able to develop through partisan staff the party’s institutional knowledge, policy arguments, and ability to exercise oversight on the other party.

1.1.4 The House should create bipartisan opportunities to take committee-based congressional delegation trips

The Select Committee suggested that the House create opportunities for committee Members to learn more about the federal programs within their committees’ jurisdictions by taking domestic, bipartisan trips together (see Chap 10, Recommendation 6). These trips by congressional delegations are often called CODELs. The Select Committee further recommended allowing personal office staff (staff for each committee member’s individual office, as distinct from staff who work for the committee) to also participate in these trips, noting that the ability for staff to work together on a bipartisan basis is also important (see Chap 2, Recommendation 3).

Bipartisan trips were the sixth highest-rated congressional reform by NICD’s panel of experts, receiving an average rating of 3.33. The bipartisan trips the NICD panel considered were not restricted to committee-based versions. They thought these trips generally are useful for building bipartisan rapport and problem-solving ability. Our panel generally agreed, however, on the power of doing these kinds of reforms are at the committee level.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: When describing their most important and productive bipartisan relations, it is striking how often Members of Congress credit joint trips to the formation of those relationships. These trips, they observe, provide longer and deeper engagement on substantive topics as well as opportunities for more personal interaction. Members say the result is greater trust and rapport. As Jason Grumet, president of the Bipartisan Policy Center said at the Select Committee hearing on bipartisanship, “One of the most effective and practical opportunities to build shared knowledge and trust among Members are bipartisan fact-finding trips.”

The Case Against: CODELs are sometimes described as junkets for a reason, some argue. Members are simply enjoying the high life on the taxpayers’ dime. Increased support for joint trips could cause further erosion of public confidence in Congress.

1.2 Bipartisan Leadership Agenda Setting Meetings

Of the 12 reforms that NICD identified, the one that received the highest average rating (3.91) by the more than one dozen experts NICD convened was the recommendation that the leadership of both parties meet regularly to seek agreement on at least one piece of legislation that should be pursued on a bipartisan basis. It should occur at least monthly and be held off-the-record and without the public or press present. Depending on the topics, the meeting should frequently include committee chairmen and ranking members (the senior Member of the committee from the minority party).

The Select Committee did not make this one of its recommendations.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Although we have a system the Founders purposely designed to require broad support to pass bills into law, little in today’s congressional structure and processes provides an opportunity to develop such measures on a collaborative, bipartisan basis. Supporters argue that for Congress to discharge its constitutionally mandated functions more effectively, it is essential that leadership spend time together identifying measures sufficiently wise to attract support from both parties. This is particularly important, some argue, because leadership now takes a much more active role relative to committees in setting the legislative agenda than used to be the case. This more leadership-driven congressional agenda is inherently more partisan. The Senate Majority Leader or the Speaker of the House, chosen by the majority, are working to protect their majorities. But, supporters argue, these bipartisan, joint leadership meetings could increase the prospects for bipartisan action where it really counts. This would be particularly true where each party controls one of the chambers or where a chamber is very closely split which has been typical for decades.

The Case Against: Those who support greater bipartisanship but don’t support frequent joint leadership meetings argue that there simply isn’t an effective way of formalizing this. Joint leadership meetings do happen on an as-needed basis. Some suggest there’s not a plausible way to make leaders do it more regularly and in a genuine spirit of bipartisanship. Some supporters of bipartisanship also object to the behind-closed-doors aspects of this recommendation. Meetings with only leadership making critical decisions are at odds, the argument goes, with a system by, for, and of the people, in which the full House and Senate are seen as the most representative of the people. The public and interest groups should have an opportunity to weigh in early enough in the process to make a difference.

Those who don’t support greater bipartisanship argue that both majority and minority leaders are appropriately partisan. The two parties offer deeply different visions and policies for the country. They should not be hesitant to advocate for them, and when voters reward a party with a majority, they should move decisively to enact it, even over the objections of the minority.

1.3 Bipartisan Congressional Retreats Every Two Years

The recommendation that Congress hold retreats every two years for all Members at the beginning of each new Congress received an average rating of 3.55 among NICD’s group of more than a dozen experts, the fourth highest rating of the twelve considered. NICD’s panel suggested that the retreats draw from the best of the “Hershey” model originally led by Representatives LaHood and Skaggs that occurred at the beginning of each new Congress from 1997—2003 (the first few were held in Hershey, PA). Members should spend several days offsite within several hours of Washington with family members invited. The program should include speakers, opportunities to socialize, and working sessions to make recommendations for improving bipartisan relations. The retreat should be planned by a bipartisan committee appointed by Congressional leadership. The Select Committee also adopted this reform (See Chap 2, Recommendation 2).

PROS & CONS

The Case For: The Select Committee noted that the congressional partisan divisions that we see publicly begin in private, fostered by institutional practices. Many sessions of New Member Orientation are conducted separately for Republicans and Democrats. Each year, each of the party caucuses have their own separate retreats. Both New Member Orientation and the party caucus retreats foster relationship building, but only within each party. The recommended bipartisan congressional retreats would change that. The several-day length facilitates more interaction. The offsite location limits distractions. The inclusion of family significantly deepens the connections that are made. As Members meet each other’s family, and as Members’ families interact and become friends during the family activities, they will find it easier to recognize all that they share. Former Representative Ray LaHood co-led the Hershey retreats in the late 1990s and early 2000s and testified in the Select Committee hearing on bipartisanship about their effect. “As a result of that [retreat], people really came away with the idea that they knew their colleagues better than they did before,” he said. He concluded, “You know, it is pretty hard to trash somebody on the other side when you know their spouse, or you know their kids.”

The Case Against: The political optics of Members of Congress socializing at a retreat location concern some. A retreat for hundreds of people is expensive. The Hershey retreats had outside funding. Even some supporters agree that it would be inappropriate to use taxpayer dollars. Perhaps the biggest critique of this approach is that it was already tried. Participants and funders did not see a sufficiently meaningful improvement in bipartisan relations and civility when they were conducted before. They did not continue because participation and support waned over time and both are required to sustain such an ambitious gathering.

1.4 Less Travel Time

Today, the congressional work week in DC typically starts Tuesday afternoon and ends Thursday afternoon to allow Members to be back in their districts meeting with constituents on either end of the week. Various reforms would move to a full five-day work week that starts Monday morning and concludes Friday afternoon. These reforms would also include longer blocks of time back in the district to reduce travel time while still providing time for constituent work there. For example, Congress could alternate full work weeks in DC and full weeks back in the district. Alternatively, Congress could have two-consecutive workweeks in DC and then one full workweek in the district. NICD asked its group of experts to rate this two-week-in-DC, one-week-in-home-districts reform. It received an average rating of 3.4, the fifth-highest rating of the twelve ratings they considered. The Select Committee also recommended changing the calendar to increase full working days and decrease travel days (See Chap 12, Recommendation 4).

Below, we describe three variations on this recommendation. We start with the two-full-congressional-weeks, one-full-district-week schedule NICD’s panel recommended. We then consider the one-week-in-Congress, one-week-in-the-home district, and the three-week-in-Congress, one-week-in-the-home-district schedule.

1.4.1 Two full congressional work weeks, one full district work week

In this version, Congress would be in session for two nearly full, consecutive workweeks. The third week would be back in the district. The congressional session the first week would not start until Monday afternoon so that most Members could depart their districts Monday morning. That first week in session would continue until the end-of-the-day on Friday. The second week in session would start first thing Monday morning but would end by early Friday, giving time for most Members to get home that night. This would mean that third workweek, which is back in the district, would have a full weekend just before and after it. NICD’s experts rated this reform highly because they believe it would achieve three objectives. First, it would provide significantly more opportunity for Members to engage with each other and forge better relations. Second, it would provide more consecutive time together to build momentum critical to the hard work of fashioning sound solutions wise enough to attract bipartisan support. Third, it would provide efficiency gains by significantly cutting the time that Members spend traveling back and forth from their congressional districts each week.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Here, we elaborate on three main reasons are offered for this schedule. First, it would provide significantly more opportunity for Members to engage with each other and forge better relations. Under the current schedule, much of the Members’ time is consumed with formal committee meetings, floor votes, and individual Member meetings with interest groups and constituents. The proposed schedule would provide more time for Members to engage each other informally and build healthy bipartisan relationships and increase their ability to effectively solve problems together. Because the first week in session ends late Friday and the second week begins first thing Monday morning, it would encourage more Members to stay in DC for one out of three weekends, creating further opportunities to forge better relations. Proponents argue that this is more like how the congressional schedule used to be. The result, they argue, was a Congress whose Members worked together more effectively.

Second, supporters observe that less than three full days in a workweek under the current schedule is simply insufficient time to make sound policy on the most pressing legislative questions facing a nation of over 300 million people. The advantage of two consecutive full works for getting the work done goes beyond the increase in the absolute number of hours spent in session legislating. Congressional veterans argue that having significant time in succession is critical for the momentum required to solve problems and develop sound legislation. Past legislative leaders argue that when Members only have a few days together in session, separated by four or five days apart, progress toward passing sound and important legislation is severely restricted.

Third, advocates point to the efficiency gains from significantly cutting the time Members spend traveling back and forth from their congressional district each week. For some Members whose congressional district is close to Washington, DC, the travel is not particularly burdensome. For the vast majority, weekly trips home mean that they lose a significant amount of time to travel. If they need to fly, Members will typically lose at least four hours when one includes getting to the airport, going through security and traveling from the airport to a Member’s final destination. For Members from districts further from DC and/or without major airports, a one-way trip can easily consume more than six hours. With a conservative average of a four-hour one-way trip under the current practice of weekly returns to the district, the average Member is losing eight hours to travel, the equivalent of losing one full work-day per week.

Keith Allred shared NICD’s analysis of the efficiencies of the two-week-in-Congress, one-week-in-the district schedule at the Select Committee hearing on bipartisanship. If a Member chooses to go home each weekend, this schedule would reduce travel time by 33% over the current schedule because of the one-in-three full weeks when the Member stays in the district. If one assumes an average of four hours to get to the airport, go through security, fly, and travel from the airport, the average travel time savings per week is 2.7 hours. If a Member chooses to stay in DC for the weekend in between the first and second week in session, it would reduce travel time by 67%, an average savings in travel time of 5.3 hours per week. The time saved traveling would give Members more time both to do their constituent work back in their district and foster relations and do the work of legislating in DC, not to mention sparing them the wear-and-tear from travel. In addition to time savings, reduced travel reduces the associated costs and carbon footprint.

See NICD’s full analysis of time savings

Table 1:

Travel Time Savings for Two-Weeks in Session, One Week in Congressional District (CD)

| In Washington DC (DC) | In Congressional District (CD) | Travel Time |

| Current Schedule | 2 weeks in session, 1 in CD All Weekends in CD | 2 weeks in session, 1 in CD 2 Weekends in CD |

|---|---|---|

| WEEK 1 | ||

| 1st one-way trip: Travel to DC | 1st one-way trip: Travel to DC | 1st one-way trip: Travel to DC |

| Week 1: In session | Week 1: In session | Week 1: In session |

| 2nd one-way trip: Travel CD | 2nd one-way trip: Travel to CD | No travel |

| Weekend 1: In CD | Weekend 1: In CD | Weekend 1: In DC |

| WEEK 2 | ||

| 3rd one-way trip: Travel to DC | 3rd one-way trip: Travel to DC | No travel |

| Week 2: In session | Week 2: In session | Week 2: In session |

| 4th one-way trip: Travel to CD | 4th one-way trip: Travel to CD | 2nd one-way trip: Travel to CD |

| Weekend 2: In CD | Weekend 2: In CD | Weekend 2: In CD |

| WEEK 3 | ||

| 5th one-way trip: Travel to DC | No travel | No travel |

| Week 3: In session | Week 3: Not in session, in CD | Week 3: Not in session, in CD |

| 6th one-way trip: Travel to CD | No travel | No travel |

| Weekend 3: In CD | Weekend 3: In CD | Weekend 3: In CD |

| Total trips: 6 one-way/3 round | Total trips: 4 one-way/2 round | Total trips: 2 one-way/1 round |

| Total travel hours for 3 wks: 24* | Total travel hours for 3 wks: 16* | Total travel hours for 3 wks: 8* |

| Total travel hours saved in 3 wks: 8* | Total travel hours saved in 3 wks: 16* | |

| Travel Time Saved: 33% | Travel Time Saved: 67% | |

*Assumes average 4-hour one-way trip, including traveling to airport, security, traveling from airport

The Case Against: The two-weeks-in-session, one-week-home schedule will impose additional hardship on Members’ family lives. The longer periods away from home would be particularly hard for families with children at home. Under the current schedule, service in the Congress is already an enormous challenge for families. Making it even harder might also affect representation. Fewer people with children at home might chose not to serve.

1.4.2 One full congressional work week, one full district work week

The second reform schedule is simply to alternate one full congressional work week with one full district work week. Under this schedule, the week in session would begin Monday morning and end late Friday, like a typical work week.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Because it avoids back-to-back full work weeks in DC, some argue, this schedule would be better for Members’ family life while still reducing travel time and increasing time to work both in Congress and back in the home district. NICD’s analysis shows that this schedule cuts travel time in half. That would be an average savings in travel time each week of four hours, assuming four total hours for a one-way trip.

See NICD’s full analysis of time savings

Table 2:

Travel Time Savings for One-Week in Session, One Week in Congressional District (CD)

| In Washington DC (DC) | In Congressional District (CD) | Travel Time |

| Current Schedule | 1 week in session, 1 in CD |

|---|---|

| WEEK 1 | |

| 1st one-way trip: Travel to DC | 1st one-way trip: Travel to DC |

| Week 1: In session | Week 1: In session |

| 2nd one-way trip: Travel CD | 2nd one-way trip: Travel to CD |

| Weekend 1: In CD | Weekend 1: In CD |

| WEEK 2 | |

| 3rd one-way trip: Travel to DC | No travel |

| Week 2: In session | Weekend 1: In CD |

| 4th one-way trip: Travel to CD | No travel |

| Weekend 2: In CD | Weekend 2: In CD |

| Total trips: 4 one-way/2 round | Total trips: 2 one-way/1 round |

| Total travel hours for 2 wks: 16* | Total travel hours for 2 wks: 8* |

| Total travel hours saved in 2 wks: 8* | |

| Travel Time Saved: 50% | |

*Assumes average 4-hour one-way trip, including traveling to airport, security, traveling from airport

The Case Against: Those who prefer the two or three consecutive weeks in session argue that while the one-week-in-session, one-week-at-home schedule delivers travel time savings, it does not do enough to increase the amount of time in session. This means less time to foster Member relations to improve civility and bipartisanship and fewer absolute days and days in succession required to craft sound policy.

1.4.3 Three full congressional work weeks, one full district work week

The third reform schedule is to have three full congressional work weeks consecutively, followed by one full work week in the district.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Supporters argue that it simply provides the most time for the two critical functions of spending more time together to foster constructive relationships and to have more consecutive days spent doing Congress’s core job of legislating. The one full week out of four spent back in the district reduces travel time for Members by 25% relative to the current schedule. Four a typical one-way trip that takes a total of four hours, that means an average weekly savings of two hours per week.

See NICD’s full analysis of time savings

Table 3:

Travel Time Savings for Three-Weeks in Session, One Week in Congressional District (CD)

| In Washington DC (DC) | In Congressional District (CD) | Travel Time |

| Current Schedule | 3 weeks in session, 1 in CD If Spend All Weekends in CD |

|---|---|

| WEEK 1 | |

| 1st one-way trip: Travel to DC | 1st one-way trip: Travel to DC |

| Week 1: In session | Week 1: In session |

| 2nd one-way trip: Travel CD | 2nd one-way trip: Travel to CD |

| Weekend 1: In CD | Weekend 1: In CD |

| WEEK 2 | |

| 3rd one-way trip: Travel to DC | 3rd one-way trip: Travel to DC |

| Week 2: In session | Week 2: In session |

| 4th one-way trip: Travel to CD | 4th one-way trip: Travel to CD |

| Weekend 2: In CD | Weekend 2: In CD |

| WEEK 3 | |

| 5th one-way trip: Travel to DC | 5th one-way trip: Travel to DC |

| Week 3: In session | Week 3: In session |

| 6th one-way trip: Travel to CD | 6th one-way trip: Travel to CD |

| Weekend 3: In CD | Weekend 3: In CD |

| WEEK 4 | |

| 7th one-way trip: Travel to DC | No Travel |

| Week 4: In session | Week 4: Not in session, in CD |

| 8th one-way trip: Travel to CD | No Travel |

| Weekend 4: In CD | Weekend 4: In CD |

| Total trips: 8 one-way/4 round | Total trips: 6 one-way/3 round |

| Total travel hours for 4 wks: 32* | Total travel hours for 2 wks: 24* |

| Total travel hours saved in 2 wks: 8* | |

| Travel Time Saved: 25% | |

*Assumes average 4-hour one-way trip, including traveling to airport, security, traveling from airport

The Case Against: Those opposed argue that this schedule delivers too little efficiencies from reduced travel time. They also argue that three full work weeks in a row away from home creates too great a burden on families. Finally, opponents argue that this schedule reduces too drastically the time to spend with constituents back in the district so critical to representing those constituents well.

1.4.4 The overall reform of reducing travel time by scheduling full work weeks in session and in the district.

Having considered three different specific versions of a reform schedule, it will also be useful for Congress to hear your views of the Select Committee’s recommendation that, whatever the specific version, the schedule should be changed to increase full working days and reduce travel time.

1.5 Bipartisan Members-Only Space

The Select Committee recommended establishing a dedicated space in the U.S. Capitol for private, bipartisan discussions (see Chap 2, Recommendation 1). No physical space in the U.S. Capitol Complex exists today for Members to gather on a bipartisan basis beyond the glare of today’s heated partisan environment. The House floor and the area leading to it are often filled with journalists and television cameras, making candid bipartisan conversation difficult. Members can have private, confidential conversations in party caucuses and their own party’s cloak room, but those are explicitly places where only conversation within one’s own party can happen. The Select Committee recommends that the space be easily accessible, preferably close to the House floor and open only to Members of both parties.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: While it’s common for the general public and the press to criticize Congress for how partisan it is, we often fail to realize how much political polarization outside Congress influences how partisan Congress is. Members report having scorn heaped upon them on social media, for example, if they’re seen having a collegial conversation with someone from the other party in one of the public spaces on Capitol Hill. This influence of the most extreme among us talking loader and longer than the rest of us, combined with more polarized parties engaged in congressional processes and schedules that also reinforce partisanship, create an urgent need for a space in which Members can retreat from the partisan winds to converse and reason together.

The Case Against: Some argue that more transparency is needed in Congress, not more opportunities for closed-door discussions. Some also argue that the only place were confidential conversations are needed is for Members of the same party to collaborate on how they will advance their party’s vision and policies and defeat those of the opposing party, like the private conversations that already occur in their party’s cloakroom or caucus meetings.

1.6 Bipartisan Freshman Orientation

It comes as a surprise to newly elected Members of Congress that many of their Freshman Orientation sessions are conducted separately for Republicans and Democrats. Most Americans are also surprised to hear their newly elected Representatives’ stories of seeing colleagues from the other party entering separate buses to take them to separate locations for sessions. The Select Committee has made two recommendations to help foster greater bipartisanship during Freshman Orientation.

1.6.1 Conduct in Nonpartisan Way

The Select Committee has recommended that Freshman Orientation be conducted in a nonpartisan way with courses and services being offered to Republicans and Democrats together (see Chap 4, Recommendation 2).

The Committee has also recommended that sessions be recorded and made available electronically for viewing later. Orientation comes at an extraordinarily intense time when newly elected Members of Congress face multiple competing demands for their time as they prepare to assume their duties. Most find it necessary to miss some of the orientation sessions but would like to view them later.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: As the Select Committee wrote in their report, “Partisan training discourages collaborative partnerships between Members, many of whom feel they were sent to Washington to help ‘fix’ partisan dysfunction. Separating Members by party only furthers the polarized mentality that many find detrimental to the institution.”

The Case Against: Some argue that Members of Congress were elected to advance the vision and policies of their party and defeat those of the other party. It is more important, opponents argue, for freshman to foster relationships with fellow party members with whom they’ll join in this work than to establish relations with those who want something different for the country.

1.6.2 Offer a Course on Practices to Promote Civility and Respect

The Select Committee recommended that Freshman Orientation go beyond merely conducting sessions with Republicans and Democrats together rather than separately. It has also recommended that an orientation session be offered on House Rules of Decorum and Debate and other practices to promote civility in Congress (see Chap 4, Recommendation 4). NICD’s panel of experts rated this kind of training as average of 3.0, the ninth highest rating of the twelve reforms they considered.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: As the Select Committee discussed in its report, in many ways state legislatures provide more robust onboarding and training than the U.S. Congress does. NICD has conducted these kinds of sessions for more than 1,000 state legislators and 17 different state legislatures through its Next Generation program. Legislators have found them helpful generally and in two ways particularly. First, legislators find the exercises in which they describe for each other the experiences or people who have deeply shaped them are a powerful way to foster relationships based on shared human experience rather than the negative stereotypes of partisan opponents.

Second, given the highly partisan fervor of our times, they find it helpful to explore together why engaging their differences constructively is important. For example, NICD offers discussions of the Founding Fathers’ conclusion that the “Spirit of Party”, as George Washington put it in his Farewell Address, is the “worst enemy” of republics. We also offer discussions of case studies of when elected officials reached better decisions by engaging differences constructively contrasted with cases of disastrous outcomes resulting from dysfunction across differences.

The Case Against: Politeness and decorum can’t change that the two parties have fundamentally different values and objectives for the country. In an already crowded orientation, there is little point in taking time to talk about how to treat the other side better, when the truth is, the goal of each is to defeat what they see as the dangerous vision the other side has for the country while advancing their own vision.

1.7 Oxford-style Floor Debates

The Select Committee recommended a pilot program in which a bipartisan working group established by majority and minority leadership would choose topics, assign bipartisan teams, and schedule debates on the House floor (See Chap 10, Recommendation 7). To demonstrate and encourage substantive and civil debate, they would be conducted in the Oxford-style with one team arguing for and one team arguing against a proposition. The audience would vote before and after to determine who won, rather than to determine whether a piece of legislation passed (see a typical example described here).

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Also recommended in 1993 by a Joint Committee similar to the Select Committee, supporters argue that this pilot could provide a useful contrast to the highly partisan legislative floor debates today that contain little substance and demonstrate little expertise on the subject at hand. That experience could foster more substantive and civil debates in committees and floor debates, leading to wiser, bipartisan legislation.

The Case Against: While few see a real downside to an Oxford-style debate pilot, some think demonstration debates would be a weak reform relative to the forces behind the polarization of our time.

1.8 Debate and Deliberation Skills Training

To further encourage and develop the skills for substantive and civil debate, the Select Committee also recommends that Members and staff attend debate training, including Oxford-style debate, during the orientation at the beginning of each new session of Congress (See Chap 10, Recommendation 8). They also recommend that orientation workshops on how to understand opposing policy views be offered at these orientations to increase the ability of Members and staff to engage differences more constructively.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: The case for debate and deliberation skills training is similar to the case for Oxford-style floor debates. The Select Committee suggests it will improve the skills to engage each other in a substantive and civil way.

The Case Against: While few see a real downside to debate and deliberation skills training, some think it would be a weak reform relative to the forces behind the polarization of our time.

1.9 District Exchange Program

The Select Committee has recommended that the Committee on House Administration establish a district exchange program to allow Members of Congress to use their Members’ Representation Allowance (MRA) for traveling to other Members’ districts (see Chap 10, Recommendation 11). MRAs are the overall allowances each Member of the House of Representatives has to operate their offices. Each Member has wide, but not unlimited, discretion in spending the allowance to support their congressional duties and responsibilities. The purpose of this trips is to better understand the needs and concerns in other districts and foster better relationships.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: The arguments for this recommendation are similar to the arguments for committee-based congressional delegation trips discussed above. These district exchange trips provide more opportunities to forge professional and personal relationships and find common issues to work on together. These trips also provide an opportunity to gain an appreciation for the issues that fellow Members from different districts face, such as the different challenges faced in rural and urban districts. These district exchange trips provide the added benefit of improving bipartisan ability to pass legislation that works across the country when they involve a Republican and a Democrat visiting each other’s districts.

The Case Against: As with congressional delegation trips (CODELs), some criticize district exchange trips as junkets that allow Members to enjoy the high life on the taxpayers’ dime.

1.10 Joint Educational Gatherings of the Whole House

The recommendation that the whole House of Representatives meets periodically to focus on a general theme of mutual interest received an average rating of 3.27 from NICD’s panel of experts, the seventh-highest rating among the twelve reforms they considered. Like the committee-based version of this reform described in 1.1, this meeting of all Representatives could include talks and panels by experts on a topic. The topics need not be strictly related to legislative topics. To provide opportunities for bipartisan relationship building like the recommendation for congressional retreats every two years described in 1.3, the meetings should be informal. But these joint education gatherings should be held more frequently, perhaps three or four times per year. To make them easier to attend, they should be shorter than the multi-day retreats every two years, lasting perhaps a half of a day, and held in Washington, D.C. or close by.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Like the congressional retreats every two years discussed in 1.3, this reform would address the limited opportunities for social engagement across the aisle for the whole House. Because they would be shorter and would be held in, or at least closer to, Washington D.C., they would be easier for Members to attend. With greater participation and less required financial and other support, they could be more practical than the biennial retreats.

The Case Against: While less expensive than the recommendation for multi-day retreats every two years, these shorter, more modest gathering would still be expensive. Those who believe that the most important job of a Member of Congress is to advance their party’s agenda and defeat the other party’s, see this as an unwarranted use of money and time.

1.11 Joint Agenda Setting Meetings of the Whole House

The NICD panel considered the recommendation that the whole House meet regularly to discuss pressing issues of the day for the purpose of finding agreement on at least one piece of legislation that should be pursued on a bipartisan basis. This is similar to 1.5 described above, except that all Members of the House would be invited, not just the leadership of the two parties. The recommendation to do this with the whole House received an average rating of 3.17, the eighth highest rating among the twelve reforms that panel considered. The recommendation is that these meetings occur monthly or every two months and be held off-the-record. The Select Committee did not adopt this recommendation.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: Supporters argue that for Congress to discharge its constitutionally-mandated functions more effectively, it is essential that Republican and Democratic Representatives spend time together, and not just in their respective caucuses, to identify measures sufficiently wise to attract support from both parties. Since the House is the most representative body in our system of popular government, it’s appropriate and useful, supporters argue, for the full House to have such meetings.

The Case Against: Some argue that a meeting for a couple of hours of 435 Members once a month is too large and unwieldy to find agreement on complicated issues in an era of polarization. Some also argue that this kind of back room decision making outside of the public’s view is an inappropriate way to conduct the people’s business. Finally, opponents argue that the two parties offer deeply different visions and policies for the country. From this perspective, frequent bipartisan meetings to find common legislative ground serve little purpose.

1.12 Overall

In addition to your views on each specific recommendations, we’d like to report to Congress the degree to which our members support or oppose the recommendations to foster bipartisanship and civility in general.

OTHER SELECT COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONS

2.1 Make Congress More Effective, Efficient, and Transparent

In Chapter 1 of its Final Report, the Select Committee made six recommendations to make the internal processes by which legislation is drafted more effective and efficient for Representatives and their staff (See Chap 1). The recommendations include:

- Recommendation 1—Streamline the bill-writing process: Move from the four different electronic formats to the one format that is the most technologically advanced and best supported to save time and reduce mistakes.

- Recommendation 4—One click access to a list of agencies and programs that have expired and need congressional attention: $310 billion is spent each year on “zombie” programs, programs that have received congressional appropriations without first receiving congressional authorization, as the rules require. So that Congress can more efficiently and effectively oversee these programs, the Select Committee recommended streamlining information about reauthorizations through a one-stop online shop for program reauthorization deadlines.

The recommendations in this category also emphasize making Congress more transparent and accessible for citizens, as well as Members of Congress and their staff. The transparency recommendations include:

- Recommendation 2—Finalize a new system that allows the American people to easily track how amendments change legislation and the impact of proposed legislation on current law: Finalize the Comparative Print Project, which is 90% complete, and make it more widely available.

- Recommendation 3—Make it easier to know who is lobbying Congress and what they’re lobbying for: Replace the multiple convoluted lobbying registration processes currently in place by establishing a Congress-wide unique identifier for every lobbyist.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: The Congress is referred to as “the People’s Branch” because it is more representative than the Executive or the Judiciary. Within the Congress, the House is designed by the Framers to be closer to the American people than the Senate because each Member stands for re-election every two years in each of the 435 congressional districts across the nation. The reforms in Chapter 1 leverage technological developments to improve the accessibility, communication, and transparency so crucial as the House drafts legislation that serves the people’s interests.

The Case Against: Some argue that transparency doesn’t always make government more effective and efficient. Particularly given the level of partisan polarization among the minority of Americans who are deeply politically mobilized, they argue, transparency can actually create obstacles to practical, bipartisan problem solving. Even those who argue this general point about transparency, however, acknowledge that it is less specifically applicable to the particular recommendations the Select Committee made in Chapter 1.

2.2 Improve Congressional Capacity

In its Chapter 3 recommendations, the Select Committee focused particularly on improving congressional capacity. In the last several decades the funding and capacity for the Executive Branch has grown dramatically. The number of lobbyists, as well as the funding supporting lobbyists’ efforts, has also increased substantially. In contrast, congressional funding and capacity have declined over the last several decades. This has put Congress at a disadvantage in its policy making and oversight roles relative to the Executive Branch. It has also made Congress more reliant and open to influence by lobbyists.

Chapter 3 of the Select Committee’s Final Report reviews 16 recommendations to improve congressional capacity. Because a high level of staff turnover limits Congress’s capacity and effectiveness, the Chapter 3 recommendations focus on how to better attract and retain quality staff and staff who are as diverse as the nation. In particular, the recommendations focus on centralizing and standardizing staff benefits and removing administrative costs from the Members’ Representation Allowance (MRA) to make room to increase staff pay and benefits.

Three of the 16 recommendations are:

- Recommendation 1—Creating a one-stop shop Human Resources HUB: Currently among the 435 independently run Member offices, managers and staff are often unaware of the benefits and services offered to staff. By creating a one-stop resource, the Select Committee suggests that the House can better attract and retain highly qualified and representative staff.

- Recommendation 4—Raising the cap on the number of staff in Member offices: In the last several decades, the size of the constituencies Members represent, the complexity of policy issues, and the number of lobbyists have grown substantially. In order to keep pace and make the House less reliant on lobbyists, the Select Committee recommended raising the cap of 22 staff for Member offices that was set in 1975 to 28.

- Recommendation 9—Members Representational Allowance (MRA) formula should be reevaluated and updated, including a consideration of staff pay: To improve staff capacity and expertise, the Select Committee suggests the MRA be updated, including consideration of staff pay in relation to the Executive Branch and private industry.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: For Congress to fulfill effectively its policy making and oversight roles relative to the Executive Branch, the enormous disparity between dramatically growing Executive Branch funding and staff and the declining funding and staff for Congress must be addressed. Many of the Chapter 3 recommendations do an excellent job of finding ways to improve the recruitment and retention of staff through smarter and more efficient policies and processes rather than by simply increasing funding. Because of those recommendations for smarter and more efficient practices, the recommendations that would provide modest possibilities to increase funding will provide an even greater return in terms of increased congressional capacity. Even if one believes the federal government is inefficient and already too big, supporters argue, better congressional oversight of the Executive Branch, where the overwhelming and growing majority of federal dollars go, is essential to achieving a smaller, smarter federal government. To be effective, that oversight requires better ways to attract and retain quality staff.

The Case Against: Although most agree that the Select Committee did an excellent job of finding ways to better attract and retain quality staff that don’t require more funding, some still argue that at least some of the recommendations ultimately translate into more funding for the federal government when what is needed is a smaller federal government.

2.3 Overhaul the Onboarding Process and Provide Continuing Education for Members

Just after newly elected Members of Congress finish the final grueling months of their campaign, they face an intense schedule that includes orientation, finding and leasing district offices, hiring staff, and working out living arrangements. Most new Members find the onboarding support severely inadequate to the challenges they face. After orientation, there is virtually no ongoing continuing education for Members.

The Select Committee’s six recommendations for improving onboarding and continuing education are found in Chapter 4 of its Final Report. We reviewed two of the recommendations (Recommendation 2—Offer new-Member orientation in a nonpartisan way and Recommendation 4—Promote civility during new-Member orientation) in the first section of the brief on reforms to promote bipartisanship and civility.

Two of the other four onboarding and continuing education recommendations are:

- Recommendation 1—Allow newly elected Members to hire and pay one transition staff member: Currently, they are not allowed to hire and pay for any staff until they take office, leaving them without support for the many critical tasks they face.

- Recommendation 5—Create a Congressional Leadership Academy (CLA) to offer training for Members: The CLA would offer ongoing professional development to Members beyond new Member orientation including in managing their office’s personnel and budget, ethics, negotiation, collaborative problem solving, and trending policy topics.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: For new Members of Congress to be effective as soon as they are sworn in, they need the support of at least one staff person to tackle all the tasks they face between the election and taking office. Those tasks include identifying and leasing field offices in their districts and recruiting the rest of their staff. Beyond new Member orientation, it’s in everyone’s interests for Members to have training available that will help them be more efficiently manage their offices and legislate more effectively.

The Case Against: These recommendations boil down to spending more federal tax dollars which we should not do.

2.4 Make the House Accessible to All Americans

The Select Committee made three recommendations in Chapter 5 to improve how accessible the House is to Americans with disabilities. For example, Recommendation 2 is to require all broadcasts of House proceedings to provide close caption service.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: To truly be “the People’s Branch”, it needs to be equally accessible to all Americans. As the Select Committee report observes, “Individuals with disabilities who wish to meet with their representatives and congressional staff, attend or watch committee hearings, and visit the House floor should have the same ease of access as individuals without disabilities.”

The Case Against: Few argue against making the House more accessible to those with disabilities.

We do not review the Chapter 6 recommendations to modernize and revitalize House technology, the Chapter 7 recommendations for streamlining processes and saving taxpayer dollars, and the Chapter 8 recommendations for increasing the quality of constituent communications because those reforms have already been mostly adopted by the House.

2.5 Continuity of Government and Congressional Operations

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed many opportunities to make sure that Congress is prepared to continue to function during times of crisis. As in many other spheres, some of the innovations developed to cope with the pandemic suggested better ways of doing things that should continue. In Chapter 9, the Select Committee made 13 recommendations to make Congress work better for the American people, no matter the circumstances.

Seven of the recommendations focused on adopting, expanding, or improving the use of technology in the work of Congress. For example:

- Recommendation 6—The House should prioritize the approval of platforms that staff need for effective telework (e.g. remote communication software like teleconference technology), and each individual staff member should have licensed access to the approved technology: House Information Resources (HIR) and the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) should prioritize software licenses and updates reflective of congressional need.

- Recommendation 8—The House should make permanent the option to electronically submit committee reports: This temporary accommodation for COVID-19 made committee work more efficient, accessible, and transparent.

Other recommendations covered a range of additional topics such as continuity of operations plans (Recommendation 1) and crisis communications guidelines (Recommendation 4).

PROS & CONS

The Case For: In its Final Report, the Select Committee argued that, “It is especially important that Members of Congress be prepared to continue with their legislative and representational responsibilities in times of crisis.” The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that the recommendations in Chapter 9 are areas where continuity during crises should be improved.

The Case Against: While most agree that many of the continuity recommendations make sense, some raise concerns about some efforts to go to digital platforms and processes and the related threat of cyber-attacks and costs.

2.6 Reclaim Congress’ Article One Responsibilities

Chapter 10 of the Final Report focused on reclaiming Congress’ Article One responsibilities. Eight of the Select Committee’s twelve recommendations in this chapter focus on fostering bipartisanship and civil discourse, each of which we reviewed in the first section of the brief. The fact that two-thirds of the Chapter 10 recommendations focus on bipartisanship reflects how much the Select Committee and other serious observers, including NICD and its CommonSense American program, believe that rising partisan rancor is fundamentally limiting Congress’ ability to fulfill its functions as the co-equal branch that the Founding Fathers intended.

The other four recommendations in Chapter 10 share with Chapter 3 a focus on reclaiming Congress’ Article One responsibilities through building capacity. Again, the Select Committee saw these four Chapter 10 recommendations as particularly important if Congress is to be effective given that its staff and resources have been decreasing over the last several decades at the same time that the resources and influence of the Executive Branch and the tens-of-thousands of lobbyists have been dramatically increasing. Two of those four recommendations focus specifically on increasing capacity through improved staffing:

- Recommendation 9—The GAO should study the feasibility and effectiveness of a Congressional Office on Regulatory Rules and another Office of Legal Counsel: Rather than delegate rulemaking power to the Executive Branch, Congress should consider employing policy experts to help draft the regulatory rules for implementing the laws Congress passes.

- Recommendation 12—Increase capacity for policy staff capacity: The significant decline in the number of policy experts who work for Congress should be addressed at the same time that the number of lobbyists with policy expertise has significantly increased leaves Members of Congress more dependent on lobbyists.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: For Congress to effectively fulfill its policy making, oversight, and other Article One roles it is crucial that two major sources of diminished capacity be addressed. First, the partisan dysfunction paralyzing the Congress must be addressed, including through the eight reforms in Chapter 10 designed to foster bipartisanship and civility so that Congress is again capable of passing legislation wise enough to attract broad, bipartisan support.

Second, the enormous disparity created by the dramatically growing funding and staff for the Executive Branch and for lobbyists, on the one hand, and the declining funding and staff for Congress, on the other hand, must be addressed, including through the two recommendations for staff enhancements in Chapter 10. Even if one believes the federal government is inefficient and already too big, better congressional oversight of the Executive Branch, where the overwhelming and growing majority of federal dollars go, is essential to achieving a smaller, smarter federal government. To be effective, that oversight requires increased staff capacity.

The Case Against: Those who see the Congress as a central battleground in which two incompatible visions for the country contend, see the bipartisan reforms in Chapter 10 as beside the point. Many of the most committed adherents in each party believe the essential task is to defeat the other party’s dangerous agenda and advance their own party’s superior agenda. Even if their own party committed to engaging the other side with greater consideration and respect, many in both parties argue, the other side won’t return the favor, making attempts at bipartisanship futile.

Some argue that the recommendations in Chapter 10 to bolster staffing recommendations ultimately translate into more funding for the federal government when what is needed is a smaller federal government.

2.7 Reform the Budget and Appropriations Process

In Chapter 11, the Select Committee reviewed ways the budget and appropriations process can be improved. The “power of the purse” is one of the most important Article One powers that the Framers of the Constitution gave to Congress. Over time, more of the budget setting process has been moved from the Legislative to the Executive Branch. The process has also increasingly departed from Regular Order, the usual process outlined in the rules, and the established timelines for funding the government. The result is a budget process that has become more partisan, unpredictable, and prone to brinksmanship. The consequences have also been dysfunction, budgetary inefficiencies, and decreased accountability in how taxpayer dollars are spent. Often, the dysfunction includes last-minute negotiations and government shutdowns.

The Select Committee made seven recommendations in Chapter 11 to address these problems. Of those recommendations, two of the most important are:

- Recommendation 1—Require an annual Fiscal State of the Nation: This yearly discussion between the Executive and Legislative Branches is aimed at making sure that all parties are working from the same set of fiscal facts, including having access to nonpartisan information about what is contributing to the nation’s debt and deficit.

- Recommendation 4—Require an annual supplemental budget submission by the President: To allow Congress to begin its budgeting process earlier and on a sounder factual footing, the Executive Branch should be required to provide supplemental information prior to the President’s policy proposals and no later than December 1, including fiscal information on the prior and current year as well as credit re-estimates for the current year.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: In its Final Report the Select Committee observed that, “few if any appropriations bills are signed into law before the October 1 deadline. In fact, the process hasn’t been followed ‘by the book’ in decades.” The recommended reforms are a start to are more orderly, timely, and rationale exercise of Congress’ power of the purse.

Second, the enormous disparity created by the dramatically growing funding and staff for the Executive Branch and for lobbyists, on the one hand, and the declining funding and staff for Congress, on the other hand, must be addressed, including through the two recommendations for staff enhancements in Chapter 10. Even if one believes the federal government is inefficient and already too big, better congressional oversight of the Executive Branch, where the overwhelming and growing majority of federal dollars go, is essential to achieving a smaller, smarter federal government. To be effective, that oversight requires increased staff capacity.

The Case Against: Some members of each party argue that the primary reason the budget process is such a mess is because the other party is abusing the process in an inappropriate effort to advance their dangerous agenda items that they can’t otherwise pass. These reforms, they argue, will do little to fix that fundamental problem.

2.8 Improve the Congressional Schedule and Calendar

In Chapter 12, the Select Committee made five recommendations to reform how Members of Congress spend their time. We already reviewed Recommendation 4—maximizing full working days and reducing travel days—in the first section on reforms to foster bipartisanship and civil discourse.

The other four schedule recommendations focused on making Members’ time in D.C. more effective and efficient, particularly by addressing the enormous number of conflicts they face among the competing schedules for the various committees on which they serve. For example, Recommendation 1 is to establish a block schedule when committees may meet and to extend formal protections for time for committee work.

PROS & CONS

The Case For: In addition to increased demands on Congress, the change in the travel schedules of Members’ of Congress creates an urgent need for schedule reforms to create more time on task and make that time more productive. Members spend much more time traveling today because they travel back to their districts much more frequently. When Congress is in session, competing committee meetings create scheduling conflicts. The Bipartisan Policy Center found that on just one morning, 30 percent of House Members had a conflict between two or more committee meetings. The Chapter 12 recommendations address these scheduling challenges so that the House can better fulfill its responsibilities.

The Case Against: Spending time frequently in their district is important for them to fulfill their responsibility to represent their constituents. It’s also important for the family life of Members. The committee conflicts while in session fundamentally come from so many competing policy priorities and from Members wanting to be on so many committees, which these reforms don’t address.

2.9 Continuing the Work of the Select Committee in the Next Congress

NICD and more than thirty other organizations have recommended that the Select Committee for Modernization of Congress be re-established in the House in the 117th Congress that will run from 2021 to 2022. They would be charged with reviewing implementation of the recommendations it has already made and developing additional recommendations for making Congress more effective and efficient in serving the American people.

Many also support the establishment of a similar Select Committee for the Senate and/or a Joint Committee with the House and the Senate for similar purposes.