The Constitution, as amended by the Twelfth Amendment, established an Electoral College that creates a two-stage process. In the first stage, the states appoint electors. Each state is allotted a number of electoral votes equal to the state’s total number of members of Congress in the Senate and the House of Representatives. (The Twenty-Third Amendment gives the District of Columbia three electoral votes, even though it is not represented in Congress.) States have flexibility in deciding how to appoint their electors – though since the middle of the 19th century every state has done so through a popular election.

In the second stage, once the states have appointed their electors, the electors cast their ballots in the Electoral College. In modern times, electors pledge in advance to vote for one of the candidates and many states have laws requiring electors to comply with their pledge. In practice, this means that each state’s electoral votes are cast for the candidate who wins the popular election in the state. (Maine and Nebraska have a slightly different system – some of their electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the statewide election, and some are awarded to the candidate who won the most votes in each congressional district.)

This two-stage process under the Constitution provides roles for both states and Congress. The Electors Clause of Article II of the Constitution preserves considerable discretion for states in how to choose electors: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, [its] Electors.” But the Constitution also gives Congress the power to determine when electors must be chosen: “The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.” Congress has exercised that timing power in the 3 U.S.C. §§ 1-2. Section 1 requires that states appoint electors on Election Day. Section 2 creates a limited exception to that requirement: if a state holding a popular election “failed to make a choice” on Election Day, then the state can appoint electors later “in such a manner as the legislature of such state may direct.” Congress enacted that exception in 1845 to allow states that require a majority winner (rather than just a plurality, meaning the most votes of any candidate but still less than 50%) to hold run-off elections, and possibly also to give states flexibility if a natural disaster prevents people from voting on Election Day. No one in Congress at the time suggested that Section 2 might apply based on claims of voter fraud or other election improprieties.

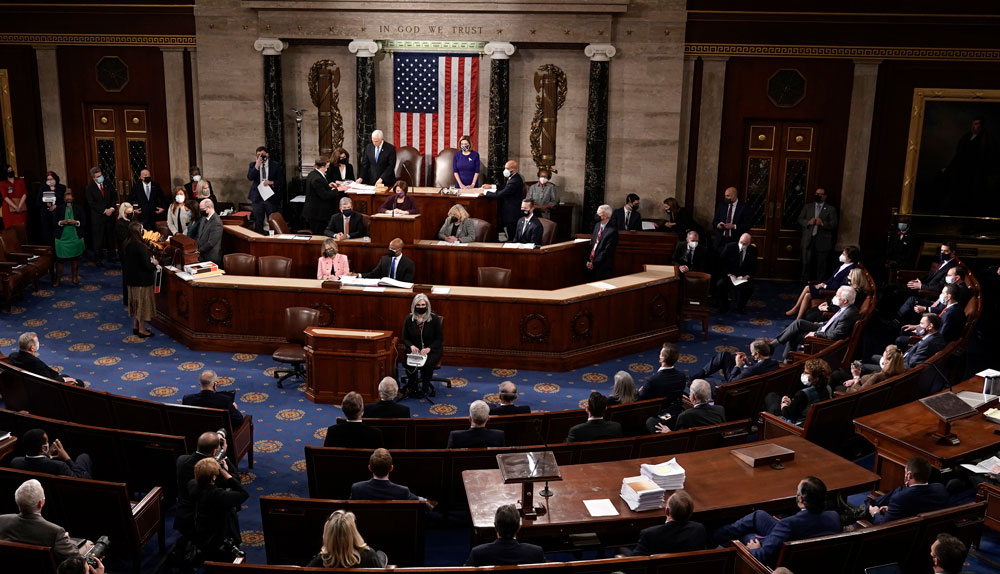

The two-stage process culminates with Congress counting the electoral votes after the electors cast them to determine which candidate has prevailed: “The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted.”

From early in our history, many have questioned Congress’s proper role in resolving disputes about presidential elections. That debate climaxed in the Crisis of 1876, in which officials from several states sent in competing slates of electors for different candidates. Ultimately, Congress was able to resolve that dispute, and Rutherford B. Hayes took office.

To “count” the 1876 electoral votes, Congress needed to determine which of these dueling submissions were valid. No one doubted that the states, and not Congress, have the constitutional responsibility for deciding how electors were to be appointed. But because it was faced with more than one piece of paper purporting to speak on behalf of the disputed states, Congress was forced to decide which submissions genuinely reflected the states’ appointment of electors. In 1876, there was no law in place governing how Congress should resolve the dispute. Because the House and the Senate were controlled by different parties, for months they couldn’t agree on how to proceed. Finally, they established an ad hoc Electoral Commission that resolved the dispute just days before Inauguration Day in 1877.

A decade after the Crisis of 1876, Congress enacted the ECA to prevent another crisis from arising in the future. The ECA establishes a process for Congress to count the electors’ votes and resolve any objections. The ECA directs Congress to treat a state’s final determination of a dispute about electors “by judicial or other methods” as “conclusive” so long as it is reached before a deadline in early December. Unfortunately, the ECA is complicated and vague and has failed to prevent members of Congress of both parties from making objections to state electoral counts that violate the ECA’s provisions. The Majority Staff of the Committee on House Administration has prepared an ECA report that provides a more complete history of the law and its applications.

The ECA first requires the governor of each state to send a certificate to Congress naming the state’s validly appointed electors, which in practice means that the governor sends a certificate naming the electors appointed through the state’s popular election. Then on January 6, Congress convenes to count the electoral votes. The ECA provides that for each state, the presiding officer along with several members of Congress called “tellers” open the certificates and announce the results. The vice president, who is the presiding officer, then calls for objections. If one member of the House and one senator sign the objection, the chambers separate to debate for two hours and then vote on the objection. The ECA’s procedures for resolving these objections are exceptionally complicated. In short:

- If Congress receives only one slate of electors purporting to be from a state that has been certified by the state’s governor, then Congress must count those electors’ votes unless they were not “regularly given” (the statute does not define this vague term.) To reject a single slate, both chambers of Congress must vote to reject it.

- If Congress receives multiple slates of electors purporting to be a from a state, and the two chambers agree on which one to count, then Congress counts those electors’ votes. But if the chambers disagree about which one to count, then Congress counts the slate that had been certified by the governor.

In taking these votes, the ECA directs Congress to treat a state’s final determination of a dispute about electors “by judicial or other methods” as “conclusive” so long as it is reached before a deadline in early December. However, as a practical matter there is no enforcement mechanism to ensure that Congress follows that direction. In recent years, Members of Congress have ignored the law’s requirements and made objections that were invalid because they were based on allegations that courts had already rejected.