Two elections in the last twenty years have brought attention to the challenge of presidential transitions. In both 2000 and 2020, the official determination by the federal government of who the president-elect was took place several weeks after the election. As a result, the additional resources provided to an incoming administration to prepare to govern under the Presidential Transition Act (PTA) were delayed.

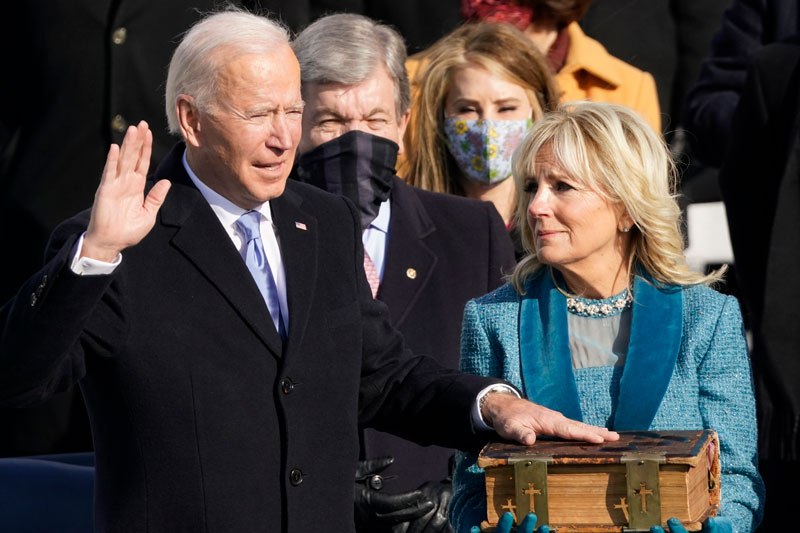

In 2020, because President Trump was contesting the results, the formal determination came almost three weeks after the election and two weeks after all media outlets had called the election for Joe Biden. Many noted that the delay in transition resources was especially consequential because the new Biden Administration was preparing to govern during a pandemic.

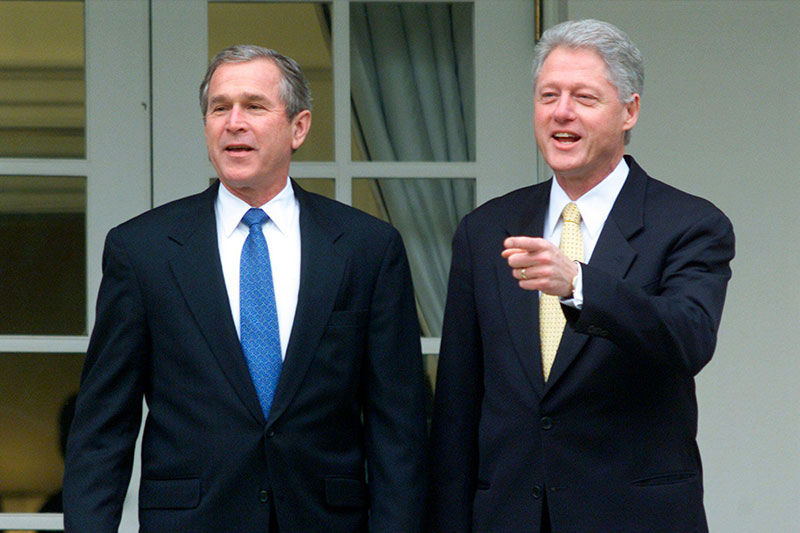

In 2000, the delay in transition resources for the incoming George W. Bush Administration was even longer. The formal determination was not made until December 14, the day that the Supreme Court effectively ended the dispute over the Florida vote in Bush v. Gore. This was a full five weeks after the election.

For most of our country’s history, the transfer of power from one presidential administration to the next was governed by a set of constitutionally grounded norms of cooperation and assistance. In 1964, motivated by a recognition that “[a]ny disruption occasioned by the transfer of the executive power could produce results detrimental to the safety and well-being of the United States and its people,” Congress formalized presidential transitions in the PTA. The act provides resources to “assure continuity in the faithful execution of the laws and in the conduct of the affairs of the Federal Government.” Those resources include increased funding, access, and in-kind support to both presidential candidates. After the election, those resources and services are significantly increased for the president-elect.

READ MORE

The executive branch structures include requiring agencies to appoint Transition Directors and prepare briefing materials, create the post of Federal Transition Coordinator, establish an Agency Transition Directors Council and a White House Transition Coordinating Council, and provide for memoranda of understanding between the General Services Administration and the transition teams.

This in-kind support begins long before the election; all (which generally means both) serious candidates receive office space, communications services, funding for printing, workshops, training for prospective appointees, and limited national security briefings. But the election itself is a significant pivot point. The president-elect receives “necessary services and facilities” that go well beyond what the campaigns had received, including funding for transition staff salaries and for travel, access to agency briefing books and personnel, fuller security briefings, and more extensive and expedited security clearances.

The enhanced support for the president-elect and the end of resources provided to the losing candidate is triggered under the PTA by the Administrator of the General Services Administration (GSA). Although the PTA directs the GSA Administrator to make the determination about the winning candidate, it provides no criteria to guide that decision.

In most presidential elections the decision has been routine and uncontroversial. With the second significant delay in 20 years and the accompanying uncertainty and controversy, a bipartisan consensus is growing for Congress to reform this provision in the PTA.

The current statute requires the GSA Administrator to “ascertain” the “apparent successful candidate.” There is significant bipartisan consensus that this provision has two major problems. The first is the problem that no criteria are provided to guide the Administrator in how to determine who the apparent successful candidate is. Second, many have noted that the GSA Administrator is not well suited for this role. The GSA oversees federal procurement and property management. The agency has nothing to do with election administration. Further, the Administrator is appointed by the current president. The GSA Administrator’s boss may be one of the two candidates (as in 2020 when the Administrator had been appointed by President Trump). In any event, the Administrator will have an extremely strong interest in the outcome of the election (as in 2000 when the Administrator had been appointed by President Clinton). In fact, the GSA Administrator appointed by President Trump noted both of these problems and urged Congress to address them in her 2020 letter making the ascertainment.

Below are three recommendations to amend the PTA to address the challenges to effective presidential transitions that were highlighted by the 2000 and 2020 elections.