The approach to advancing CCL that is currently gaining the broadest bipartisan support is Workforce Pell Grants, also known as Short-Term Pell. We start our Workforce Pell consideration with a review of the basics of Pell Grants as they work today and the arguments for and against the general idea of extending to cover shorter-term workforce education. Then we move to the specifics of Workforce Pell legislation.

The Existing Pell Grant Program

For decades, Pell Grants have been the primary way the federal government supports low- to moderate-income Americans getting college degrees. More than six million college students receive one every year, but Pell Grants are available only to a small minority of workforce development students. This is because students are only permitted to use Pell Grants to help pay for a career education program if it provides at least 600 hours of instruction over a period of no less than 15 weeks, among other requirements. Most workforce development programs are shorter than that. Created by the Higher Education Act in 1965, Pell Grants are provided to students with financial need who have typically not yet received their first bachelor’s degree. Unlike loans, Pell Grants do not need to be repaid.

Today, it is estimated that 30% – 40% of undergraduate college students receive some Pell Grant funding. The maximum Pell Grant for an academic year is $7,395 for up to 12 semesters. It is estimated that 97% of recipients had a family income of $60,000 or less in 2020-21 when Pell Grants provided more than $26 billion in aid for an average of about $4,250 per student.

Consensus Elements of Workforce Pell Legislation

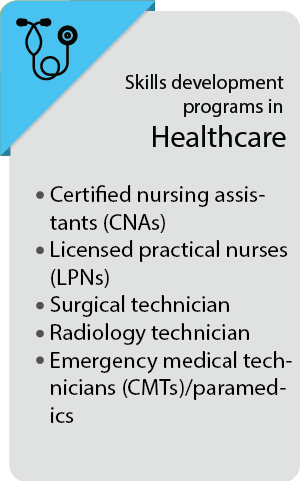

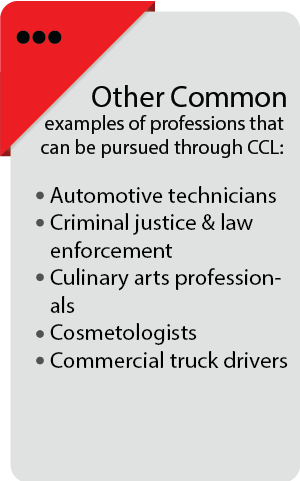

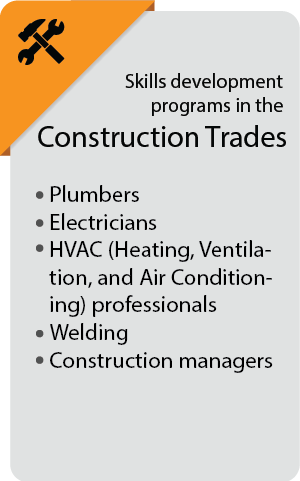

Drawing on three bills that have already been introduced, key members of Congress from both parties are actively negotiating legislation that would aim to significantly increase the number of students who can use Pell Grants to help fund completion of a career development program. The name “Short-Term Pell” arises from the focus on reducing how long a program must be to qualify. The other common name of “Workforce Pell” for this legislation comes from the focus on making the grants eligible for more programs focused specifically on developing skills needed for one’s job. Currently, Pell Grants are only eligible for programs in which one earns credits towards a degree or a certificate. Under the proposed legislation the many non-credit programs in workforce education would also be eligible.

The Republican and Democratic lawmakers who support Workforce Pell agree on three fundamental elements. First, there is bipartisan consensus on the basic question of just how much shorter programs should be and still qualify for a Pell Grant. Even many rigorous programs that provide entry to high-skill, high-paying jobs where there are worker shortages are shorter than the current minimums. For example, a typical full-time computer coding boot camp runs for 8 – 12 weeks for a total of 320 – 480 hours of instruction.

Each of the three bills already introduced would reduce the total hours required from 600 to 150 hours of total instruction time. Each bill would also reduce the time over which those hours are offered from no less than 15 weeks to no less than 8 weeks.

Typical costs of 150 – 600 hour workforce education programs

The second fundamental element on which most members of Congress agree is the size of a Pell Grant should remain proportional to the cost and length of the program, as it is today. Since the workforce education programs that would qualify are generally shorter and less expensive than a college degree, the average Short-Term Pell Grant would also be lower than the current Pell Grant average of about $4,250 per student. The US Department of Education conducted an experiment on extending Pell Grants to the same 150 hour, eight-week minimum. It found the average Pell Grant for students in these programs was $1,312.

Third, there is bipartisan agreement that new programs eligible for Short-Term Pell should include provisions to ensure the training successfully prepares graduates for, and places them in, high-skill, high-wage, or in-demand jobs.

The Case For Workforce Pell

Supporters argue the main reason to pass Workforce Pell legislation is more Americans would be able to get higher paying and more meaningful jobs as a result. They contend that, by making these programs more affordable, those who would benefit most will enroll in greater numbers. Proponents point to the finding in the Department of Education experiment that 10% more students completed 150 – 600-hour workforce education programs when Pell Grants were made available to them.

Republican and Democratic supporters also observe this is a case where the federal government can provide meaningful support that would require very little increased appropriations.

An assessment by the Congressional Budget Office estimates the cost of extending Pell Grants at $144 million per year. Supporters observe that, for a program that typically receives more than $20 billion in funding each year, adding Short-Term Pell Grants would only be a 0.72% increase in the program’s budget. Proponents highlight just how small of an additional appropriation this would require to help many Americans gain new skills and certifications. They further argue that the costs would be more than offset by the increased tax revenue and decreased social spending that would result.

Supporters argue it is difficult to find federal legislation that could have such a large impact on everyday Americans without requiring a similarly large increase in funding. They suggest the benefits of bolstering CCL generally discussed above would be realized through Workforce Pell without contributing to the federal debt and deficit problem. Those benefits include:

- For Students—Tens-of-thousands more individuals would be able to afford programs that will significantly increase their earning power

- For Businesses—More high-skill, in-demand positions would be filled

- For the Nation—The economic benefits would be felt by all Americans because worker shortages in critical areas would be addressed, productivity and economic prosperity would increase, tax revenues would increase, and unemployment and social spending would decrease

The Case Against Workforce Pell

Opponents of Short-Term Pell reject supporters’ argument that the Pell program could easily absorb an extension to shorter-term programs. They suggest the program’s history shows future changes in the economy could easily consume the existing surplus. A recent analysis by The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget using Congressional Budget Office data revealed that the Pell Grant program faces a looming funding shortfall. Currently existing surpluses of $14 billion are expected to run out by 2026, at which point growing costs will pose a significant challenge.

Opponents on the left further argue the most appropriate and highest impact use of excess funds would be to restore at least some of the real purchasing power of Pell Grants for college, which, as noted above, dropped from 79% of the average cost of public four-year institutions in 1975 to just 28% today. Some progressives have proposed doubling the maximum benefit of the Pell Grant as a first step to increasing affordability for those with the highest need.

Resistance to Short-Term Pell legislation also focuses on what opponents see as an inappropriate mix of college education and skills training. They observe that there are other federal programs (e.g., the $5.3 billion per year from Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act and the $1.4 billion per year from the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century (Perkins V) Act funds) that support workforce training. Workforce Pell would cost, according to the Congressional Budget Office, an average of $144 million a year. Pell Grants, they argue, have always been focused on supporting college education and should stay that way. If we want to provide greater financial support for CCL, then they suggest it should be done through programs dedicated to it.

Some also oppose the idea of Workforce Pell for the same reasons they generally oppose increased federal support for career-connected learning, as reviewed above, including:

- It would divert too many from pursuing a college education

- The effectiveness of workforce development programs is too low, meaning even with a Pell Grant many will be left burdened with student loans they are unable to pay back

- Earnings increases plateau soon after completing a program

- Sufficient new federal investments in CCL have already recently been made

- Financial support for skills education is better left to the businesses who would benefit

Much of the opposition to Short-Term Pell, however, is specific rather than general. This specific opposition mostly comes down to differences over the balance that should be struck between quality and access. Before reviewing those debates in the final section of the brief, we ask you to consider whether you support the general idea of Workforce Pell.