Brief Bites

Brief Bites are video summaries of the brief. If you wish to quickly consume the information in the brief watch a brief bite by clicking on the icon. They will be located in each section of the brief.

In today’s bitterly divided Congress, legislation to bolster career-connected learning (CCL) is attracting unusually high levels of bipartisan support. With Republicans narrowly controlling the House and Democrats narrowly controlling the Senate, bipartisan bills are the only ones that can pass.

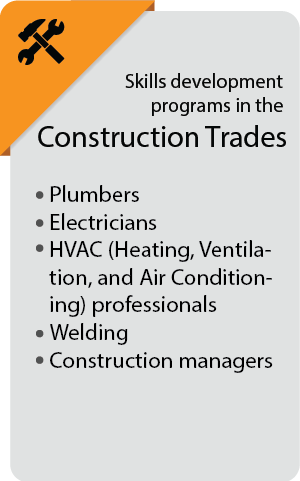

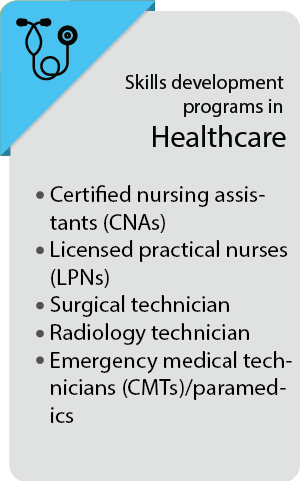

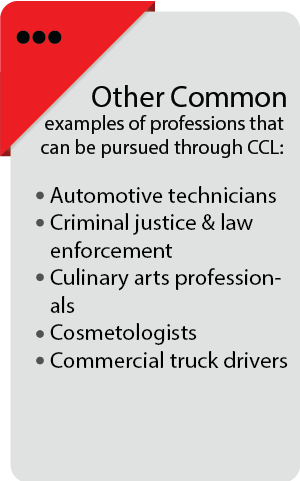

CCL differs from a traditional college education by emphasizing skills development more directly relevant to the work people do in their careers. Also called workforce development, career development, skills education, or career and technical education (CTE), these programs often focus on preparing people for immediate employment in high-demand professions that require specialized skills and knowledge. Common careers that can be pursued through CCL include those in the construction trades, health care, and in newer industries like computer programming, information technology, and clean energy (see the call out boxes throughout for examples in each area).

This brief moves from a general to a specific investigation of legislation to advance skills education that is being seriously considered in Congress. We start by reviewing the case for and against increased federal support for career development education broadly.

The brief then moves to consideration of what is often called Workforce Pell or Short-Term Pell legislation. Although other types of career and technical education bills are being discussed, Workforce Pell currently has the broadest bipartisan backing and greatest prospects for passing. Bills in this category would provide greater financial support for Americans enrolling in recognized CCL programs by making them eligible for Pell Grants. These grants are the most common source of federal support for education beyond high school and do not need to be repaid.

The review of Workforce Pell legislation starts with the general arguments for and against it. We conclude with a review of the case for and against the most important Short-Term Pell specifics where there is not yet agreement in Congress.

The Case for Greater Federal Support

At the most general level, those who support workforce education argue it is an increasingly attractive way to prepare Americans for meaningful and financially rewarding careers. They suggest greater federal support is warranted because of the benefits to the individuals who enroll in the programs, to businesses, and to the nation generally.

Benefits to Graduates

Supporters argue three important benefits for those who graduate from these programs justify increased federal support.

First, they argue that research shows skills education increases graduates’ earnings. Proponents cite a range of studies finding those who attain a certificate from a program that prepares students for a given occupation have higher rates of employment and earn roughly 10% more than those with only a high school diploma. Advocates further cite studies showing graduates themselves see their career education program as more personally and financially rewarding. (See “What the Evidence Says” below)

Second, supporters suggest workforce development is an increasingly important alternative given significant increases in the cost of college. From 1980 to 2020, the average cost per year of full-time enrollment in an undergraduate program (including tuition, fees, and room and board) grew from an inflation adjusted $10,231 to $28,775, an increase of 181%. While the costs of CCL programs can vary widely, proponents note, they typically cost between $5,000 and $15,000, making them much less expensive than college.

As the costs of college have increased, student loan debt has risen to become the second largest form of consumer borrowing in the US, trailing only home mortgage debt. In 1980, the graduating class owed an average of $12,831, adjusted for inflation. The class of 2021 averaged $31,100 in student loan debt, down from a peak of $34,398 in 2012 but still nearly 2.5 times the 1980 number.

Third, proponents argue that, in addition to costing less in terms of dollars, workforce development is also an attractive alternative because it takes much less time. Millions of Americans—including those fresh out of high school and older workers in low paying jobs—urgently need to get into higher paying and more meaningful careers. Supporters argue completing an expensive college degree simply isn’t feasible for those who can’t afford to give up work for four years. They suggest it’s appropriate to give these Americans options that are both shorter and lead more directly to higher paying jobs. Advocates argue once these workers have stabilized their financial situation, they may be in a position to seek additional credentials and education.

Benefits to Businesses

Proponents argue employers benefit significantly from CCL programs. Particularly with today’s worker shortages, the main benefit for business is a pipeline of skilled and productive employees. The United States now has 8.8 million job openings, but only 6.4 million unemployed workers.

Supporters note a growing number of employers are prioritizing skills over degrees attained. They point to an Advance CTE report that found 92% of surveyed employers were in favor of increased public funding for career and technical education.

Benefits to the Nation

Finally, proponents argue that greater federal support for CCL will generate four important benefits for the nation. First, they suggest it would create more jobs and boost economic prosperity even beyond those who graduate from these programs. Democrats are more optimistic than Republicans about an active federal role in improving the prosperity of individuals and families. Still, conservative and liberal economists agree that increasing individual productivity is one of the most fundamental drivers of a growing economy. When we produce more with the same investment of time and money, the economy grows, new jobs are created, and everyone prospers. Economists agree that a core reason the United States is the leading economy in the world is because its workers are some of the most productive.

Since the GI Bill, bipartisan agreement on the economic wisdom of investing in Americans’ productivity has been the foundation for significant federal support for college education. Supporters argue that workforce development programs can be a similarly sound investment in improving the nation’s productivity. In fact, many argue that the return on investment for career-connected learning is often even better than for college. On one side of the economic return equation, skills development programs are much shorter and less expensive for the student. On the other side of the equation, proponents suggest that these programs can still lead to substantial increases in earnings and productivity, particularly since they are so directly focused on preparing individuals for the work they will do and in industries where demand for workers is high.

Supporters argue that CCL’s boost to American prosperity is likely to be even greater going forward because it addresses the pronounced worker shortages mentioned above that the country currently faces. The lack of workers in many fields across the country, proponents argue, is acting like a brake on the American economy. They suggest that the economic returns for greater productivity will be even greater in the near term because workforce development helps place workers in areas with critical shortages of individuals with the required skills.

Supporters argue that a second benefit to the nation would be higher tax revenues and decreased social spending. These net economic benefits for everyone, proponents suggest, are the natural consequence of the increased productivity and earnings, as well as decreased unemployment, that result from workforce education. For example, supporters cite a City and Guilds Group research review that reported that for every dollar invested in career and technical education, the state of Washington received an additional $9, and Tennessee an additional $5, in increased revenues. Over a 36-year period, the review further reported, the cumulative effect of savings on social spending and increased tax revenue was $25,000 per student completing a career and technical education course.

A clear majority of Americans (61%) agree there is too much inequality in the United States. Still, Republicans and Democrats often disagree about the best ways to address it. Many Democrats believe we should increase taxes on the wealthy to fund more social spending for those in need. Many Republicans argue policies that take money from those who have succeeded through their own merit to provide benefits to those who may not have been as hard working is unfair. More importantly, Republicans argue, redistributive tax policies don’t address the root problems. In fact, conservatives contend, income redistribution policies create incentives at odds with what works for long-term individual and national prosperity.

Many Republicans and Democrats agree, however, that bolstering CCL is a wise option that rises above the long-standing partisan divide over income redistribution policies. They argue that by completing skills education programs, workers can generate greater income for themselves while also taking well-earned satisfaction from making more meaningful contributions to society. In fact, supporters argue federal policy that focuses disproportionately on support for college education to the neglect of workforce development contributes to income inequality. They suggest that simply by supporting skills education proportionately to its worth we can provide more Americans with opportunities for upward economic mobility through their own merit.

Some argue investing in career development is wiser policy than forgiving the student loans of those with four-year and graduate degrees. They point to evidence confirming that those with college and graduate degrees have higher earning power than those without those degrees, putting most in a reasonable position to repay the loans as they agreed to do. Critics of the program argue subsidizing those with higher earning power by forgiving student loans increases income inequality. To qualify under the Biden Administration’s student loan forgiveness plan that was blocked by the Supreme Court, individuals must earn less than $125,000 and married couples less than $250,000.

Proponents further argue that CCL is particularly well suited to the challenges of income inequality unique to the United States. Among developed nations, the US has one of the highest levels of income inequality as well as one of the lowest levels of investment in career development programs.

The causal connection between the two, supporters argue, is growing. The rise of new technologies in a global marketplace has created higher demand for skilled labor, and those positions come with higher wages. Supporters argue these realities of the high-tech, global economy make skills development an increasingly timely and effective means of addressing rising income inequality in the US.

Federal Support for Education and

Training After High School

Supporters argue the fourth benefit of greater workforce development support is it will lead to better recognition of the important roles these careers play in our national life. Proponents from across the partisan divide argue that for too long federal policy has emphasized college to the exclusion of the many other important training opportunities that do not require a college degree. They observe that, in the eighty years since the passage of support for college education in the GI Bill, we’ve never gotten above 40% of Americans obtaining four-year degrees. Yet, the federal government provides over $112 billion per year in on-going funding for grants, work-study, and loans for college students. In contrast, proponents observe, the federal government provides less than $7 billion per year in on-going funding for workforce development and skills education, including $5.3 billion through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) and $1.4 billion through the Strengthening Career and Technical Education Act for the 21st Century (Perkins V).

Advocates note that going to college is also privileged within our K-12 system. They suggest this results in many high school graduates for whom college was not a good fit wasting time and money in college, often without finishing but still burdened with student loan debt. Instead, supporters argue, these high school graduates could have been pursuing another career through skills education programs that would have helped them secure well paying jobs sooner for much less time and money.

Proponents suggest it’s high time we as a nation give the respect due to the majority of Americans who don’t get a degree but who make important contributions to our country. They suggest greater respect starts as a matter of federal policy, one that includes increased support for educational programs that focus directly on preparing these Americans for their careers.

The Case Against Greater Federal Support

The case for an increased federal role generally in growing the number and quality of CCL opportunities has attracted greater bipartisan support in Congress than the case against. Nevertheless, the opposition that remains is sufficient to make passing legislation challenging. Those against the federal government playing a more significant role offer six main reasons.

Diverts People from College

First, opponents argue a significant change in federal policy to make workforce development a more attractive alternative to college would be a mistake. They contend a college education remains the best path to realizing the American Dream. We should encourage our citizens to get a degree, they suggest, whether they come from low-, middle-, or high-income families and whether they come from families with no or with extensive college experience.

First, opponents argue a significant change in federal policy to make workforce development a more attractive alternative to college would be a mistake. They contend a college education remains the best path to realizing the American Dream. We should encourage our citizens to get a degree, they suggest, whether they come from low-, middle-, or high-income families and whether they come from families with no or with extensive college experience.

Because college graduates have higher average earning power, opponents suggest the emphasis on college is warranted as preparation for one’s career. Furthermore, they argue the benefits of a college education go well beyond narrow training to complete tasks at work. In college, opponents contend, one develops more generalizable competencies like critical thinking, effective communication, and an ability to engage diverse perspectives constructively. They suggest these broad capabilities are critical to individuals’ success not only in their professional lives, but also in their personal lives and in their responsibilities as citizens in a system of self-government. Opponents of greater federal CCL support suggest these broad competencies are even more important with today’s bitter partisanship. That includes giving citizens the tools to recognize today’s rampant misinformation for what it is. A survey by the American Enterprise Institute found college graduates are more civically engaged than those without a college degree.

Opponents also argue that, while more than $112 billion in annual federal support for college students may seem substantial, it’s actually far less support than we used to provide when the rapidly increasing costs of college are taken into account. For example, opponents observe that the maximum Pell Grant covers just 28% of the average costs of four-year public college, a significant drop-off from the peak of 79% in 1975. They argue that, given the superiority of a college education, the federal funding priority should be restoring support to its original purchasing power, rather than on career connected learning.

Finally, opponents argue we should be proud of our contrast with the European model. They observe that, in Europe, citizens are segregated into either a trade or a college track early on. Opponents note that those from lower income and less educated backgrounds, as well as people of color and immigrants, are disproportionately segregated into the workforce development route with little opportunity to change course later. They argue we should not embrace this kind of discrimination in America. Instead, opponents suggest we should maintain or increase our emphasis on college, including by prioritizing it over skills education so more, not fewer, go to college.

Career-Connected Learning is Too Often Low Quality and Ineffective

Opponents of increased support for CCL argue workforce education programs are too frequently low in quality. They cite studies demonstrating that many certificate programs do not deliver the promised placement in higher paying jobs. Opponents note a high proportion of programs in career education are offered by for-profit institutions, which are especially poor performing, or are in fields at the lowest end of the earnings scale (see “What the Evidence Says” below). Additionally, opponents note, research shows good information isn’t readily available to potential students to help them pick which programs will effectively boost their earnings and which won’t.

Opponents argue the most serious consequence of poor-quality workforce programs is they can actually leave students worse off financially. If the program fails to place students in higher paying jobs, those students are nevertheless saddled with student loans they can’t afford to repay.

Earnings Do Not Continue to Rise as Rapidly as for College Graduates

While some opponents acknowledge some workforce skills education programs can produce significant initial increases in earnings, they argue their earnings then tend to plateau. The more general education provided in college, they suggest, establishes a foundation for graduates to continue to grow in responsibility and earnings throughout their career.

Increases Federal Spending When We Should Be Cutting It

Opponents point to record levels of federal spending, as well as the debt and deficits that go with it, as another reason we should not increase federal support for CCL at this time.

The increase in federal spending has contributed, opponents argue, to a significant rise in inflation, making goods and services much more expensive. The Federal Reserve is working to combat inflation by increasing interest rates, which opponents observe then raises two more problems. First, it obviously increases the cost for individuals and businesses to borrow money. Second, higher interest rates mean interest payments on the federal debt are growing significantly, crowding out federal opportunities for high-priority investments or reduced taxes.

Sufficient Increases in Federal Support for CCL Have Already Been Made

Some argue now is not the time to increase federal workforce development spending given new investments have already been made over the last several years. A bill signed by President Trump in 2018 and another signed by President Biden in 2021 both included CCL funding. The 2018 bipartisan Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act, also known as “Perkins V”, is the latest in an on-going program that was first established by a 1984 bill to support career and technical education. The 2018 law provides $1.4 billion each year in on-going funding for high school and post-secondary job training programs, an increase of about $300 million per year compared to the previous Perkins bill.

The 2021 bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act CommonSense American helped pass is projected to create 700,000 jobs per year that will be needed to improve the nation’s infrastructure. Many of these new jobs will need to be filled by skilled workers. The law allocates nearly $15 billion per year for five years of one-time funding for job training and other workforce development programs.

Additional CCL Better Left to Businesses

Opponents also argue workforce development is a particular form of education in which businesses should take a more prominent role. If a program is specifically oriented to making workers more productive, and if the economic benefits for businesses are as high as claimed, they argue, then business should make the investments needed to foster the additional skills education.

Supporters and opponents each cite research they claim supports their arguments about the effectiveness of career-connected learning in placing graduates in higher paying jobs. So, what does the evidence actually say?

A rigorous review of 17 existing studies and subsequent analysis using three separate government datasets was performed by the Urban Institute. The review notes that given the great variety in programs, there is substantial variability in how effectively they place graduates in jobs that pay better. Still, on average the review found a 10% increase in earnings across the data. This comprehensive review of much of the existing evidence also confirms several factors associated with poorer outcomes. In general, the shorter the program, the less graduates’ earnings increase. Programs provided by for-profit institutions tend to generate less value than those from community colleges, and significant differences exist in the returns to certificates depending on the field of study.

One of the studies most often cited by opponents of CCL is one published by the Brookings Institution after the Urban Institute review was conducted. The recent Brookings study investigated short-term programs eligible for federal student loans. The study’s results indicate graduates of these short-term certificate programs do not earn more than the average 25-34-year-old with just a high school degree. This study examines the results for a sample 103 short-term programs, of which 74 are for-profit institutions, 25 public institutions, and four private non-profits. Of the 103 programs assessed, 47 were in cosmetology, which is one of the fields where earnings increases are the lowest. Additionally, for-profits were found to offer certificates that led to generally lower earnings than those offered by public institutions. Given the sample of programs studied, the Brookings’ findings are basically consistent with the Urban Institute’s findings discussed above.

The approach to advancing CCL that is currently gaining the broadest bipartisan support is Workforce Pell Grants, also known as Short-Term Pell. We start our Workforce Pell consideration with a review of the basics of Pell Grants as they work today and the arguments for and against the general idea of extending to cover shorter-term workforce education. Then we move to the specifics of Workforce Pell legislation.

The Existing Pell Grant Program

For decades, Pell Grants have been the primary way the federal government supports low- to moderate-income Americans getting college degrees. More than six million college students receive one every year, but Pell Grants are available only to a small minority of workforce development students. This is because students are only permitted to use Pell Grants to help pay for a career education program if it provides at least 600 hours of instruction over a period of no less than 15 weeks, among other requirements. Most workforce development programs are shorter than that. Created by the Higher Education Act in 1965, Pell Grants are provided to students with financial need who have typically not yet received their first bachelor’s degree. Unlike loans, Pell Grants do not need to be repaid.

Today, it is estimated that 30% – 40% of undergraduate college students receive some Pell Grant funding. The maximum Pell Grant for an academic year is $7,395 for up to 12 semesters. It is estimated that 97% of recipients had a family income of $60,000 or less in 2020-21 when Pell Grants provided more than $26 billion in aid for an average of about $4,250 per student.

Consensus Elements of Workforce Pell Legislation

Drawing on three bills that have already been introduced, key members of Congress from both parties are actively negotiating legislation that would aim to significantly increase the number of students who can use Pell Grants to help fund completion of a career development program. The name “Short-Term Pell” arises from the focus on reducing how long a program must be to qualify. The other common name of “Workforce Pell” for this legislation comes from the focus on making the grants eligible for more programs focused specifically on developing skills needed for one’s job. Currently, Pell Grants are only eligible for programs in which one earns credits towards a degree or a certificate. Under the proposed legislation the many non-credit programs in workforce education would also be eligible.

The Republican and Democratic lawmakers who support Workforce Pell agree on three fundamental elements. First, there is bipartisan consensus on the basic question of just how much shorter programs should be and still qualify for a Pell Grant. Even many rigorous programs that provide entry to high-skill, high-paying jobs where there are worker shortages are shorter than the current minimums. For example, a typical full-time computer coding boot camp runs for 8 – 12 weeks for a total of 320 – 480 hours of instruction.

Each of the three bills already introduced would reduce the total hours required from 600 to 150 hours of total instruction time. Each bill would also reduce the time over which those hours are offered from no less than 15 weeks to no less than 8 weeks.

Typical costs of 150 – 600 hour workforce education programs

The second fundamental element on which most members of Congress agree is the size of a Pell Grant should remain proportional to the cost and length of the program, as it is today. Since the workforce education programs that would qualify are generally shorter and less expensive than a college degree, the average Short-Term Pell Grant would also be lower than the current Pell Grant average of about $4,250 per student. The US Department of Education conducted an experiment on extending Pell Grants to the same 150 hour, eight-week minimum. It found the average Pell Grant for students in these programs was $1,312.

Third, there is bipartisan agreement that new programs eligible for Short-Term Pell should include provisions to ensure the training successfully prepares graduates for, and places them in, high-skill, high-wage, or in-demand jobs.

The Case For Workforce Pell

Supporters argue the main reason to pass Workforce Pell legislation is more Americans would be able to get higher paying and more meaningful jobs as a result. They contend that, by making these programs more affordable, those who would benefit most will enroll in greater numbers. Proponents point to the finding in the Department of Education experiment that 10% more students completed 150 – 600-hour workforce education programs when Pell Grants were made available to them.

Republican and Democratic supporters also observe this is a case where the federal government can provide meaningful support that would require very little increased appropriations.

An assessment by the Congressional Budget Office estimates the cost of extending Pell Grants at $144 million per year. Supporters observe that, for a program that typically receives more than $20 billion in funding each year, adding Short-Term Pell Grants would only be a 0.72% increase in the program’s budget. Proponents highlight just how small of an additional appropriation this would require to help many Americans gain new skills and certifications. They further argue that the costs would be more than offset by the increased tax revenue and decreased social spending that would result.

Supporters argue it is difficult to find federal legislation that could have such a large impact on everyday Americans without requiring a similarly large increase in funding. They suggest the benefits of bolstering CCL generally discussed above would be realized through Workforce Pell without contributing to the federal debt and deficit problem. Those benefits include:

- For Students—Tens-of-thousands more individuals would be able to afford programs that will significantly increase their earning power

- For Businesses—More high-skill, in-demand positions would be filled

- For the Nation—The economic benefits would be felt by all Americans because worker shortages in critical areas would be addressed, productivity and economic prosperity would increase, tax revenues would increase, and unemployment and social spending would decrease

The Case Against Workforce Pell

Opponents of Short-Term Pell reject supporters’ argument that the Pell program could easily absorb an extension to shorter-term programs. They suggest the program’s history shows future changes in the economy could easily consume the existing surplus. A recent analysis by The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget using Congressional Budget Office data revealed that the Pell Grant program faces a looming funding shortfall. Currently existing surpluses of $14 billion are expected to run out by 2026, at which point growing costs will pose a significant challenge.

Opponents on the left further argue the most appropriate and highest impact use of excess funds would be to restore at least some of the real purchasing power of Pell Grants for college, which, as noted above, dropped from 79% of the average cost of public four-year institutions in 1975 to just 28% today. Some progressives have proposed doubling the maximum benefit of the Pell Grant as a first step to increasing affordability for those with the highest need.

Resistance to Short-Term Pell legislation also focuses on what opponents see as an inappropriate mix of college education and skills training. They observe that there are other federal programs (e.g., the $5.3 billion per year from Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act and the $1.4 billion per year from the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century (Perkins V) Act funds) that support workforce training. Workforce Pell would cost, according to the Congressional Budget Office, an average of $144 million a year. Pell Grants, they argue, have always been focused on supporting college education and should stay that way. If we want to provide greater financial support for CCL, then they suggest it should be done through programs dedicated to it.

Some also oppose the idea of Workforce Pell for the same reasons they generally oppose increased federal support for career-connected learning, as reviewed above, including:

- It would divert too many from pursuing a college education

- The effectiveness of workforce development programs is too low, meaning even with a Pell Grant many will be left burdened with student loans they are unable to pay back

- Earnings increases plateau soon after completing a program

- Sufficient new federal investments in CCL have already recently been made

- Financial support for skills education is better left to the businesses who would benefit

Much of the opposition to Short-Term Pell, however, is specific rather than general. This specific opposition mostly comes down to differences over the balance that should be struck between quality and access. Before reviewing those debates in the final section of the brief, we ask you to consider whether you support the general idea of Workforce Pell.

Since the congressional Short-Term Pell debate centers on finding the right balance between quality and access, so does our consideration of specific legislative provisions currently being debated. Below we review five different approaches to assuring adequate levels of quality. The preferences among Workforce Pell supporters range from using modest versions of one or two of these approaches to the robust use of all five.

While everyone wants Pell Grants to support quality programs that successfully place students in higher paying jobs, more quality requirements may make workforce development less accessible in four possible ways:

- Fewer programs may qualify—Fewer qualifying is by design. The purpose of the quality provisions is to ensure that low–quality programs aren’t supported by Short-Term Pell.

- Fewer programs may apply—To become eligible for Pell Grants, workforce development program administrators must apply and demonstrate they meet each quality standard Congress requires. Many programs are already stretched for resources. The more cumbersome the process, the fewer programs may apply. Even if they do successfully apply, some may find the ongoing work of maintaining eligibility sufficiently burdensome that they forgo their eligibility.

- Programs may accept fewer of the students who need it most—Many of the students who would benefit most from workforce education are also the most difficult to support and successfully place in higher paying jobs. If the quality standards are too high, it may create incentives for programs not to accept these more challenging students.

- May increase tuition and fees—The administrative costs of documenting fulfillment of quality requirements may also be passed along to students in the form of higher tuition and fees.

As you review the five approaches to quality assurance described below, consider whether each requirement, alone or in combination with the others, strikes the right balance with accessibility.

1. Excluding For-Profits

One means by which the first bill introduced in Congress aims to make certain Pell eligible programs are high quality is to make all for-profit educational institutions who offer workforce development courses ineligible. That first bill is the Senate’s Jumpstart Our Businesses by Supporting Students (JOBS) Act, versions of which were first introduced several years ago. The two other major Short-Term Pell bills were both introduced in the House. Each House bill would make for-profits eligible for Pell Grants if they, and all other career development programs, meet other quality requirements discussed below. The first House Short-Term Pell bill is called the Promoting Employment and Lifelong Learning (PELL) Act. The second one is the Jobs to Complete Act.

Many believe Short-Term Pell legislation would have already passed were it not for the question of how to treat for-profit institutions. For-profit four-year programs can be more accessible than traditional four-year public colleges or private non-profit colleges because they often have lower academic requirements for admittance and have more flexible schedules for working students. However, for-profit four-year college programs have had significant quality problems. The for-profit quality concerns are even greater for skills education courses.

Case For

Supporters of prohibiting for-profit institutions from Workforce Pell eligibility argue there are higher quality concerns with these institutions for a good reason. They simply point to the considerable track record of poor for-profit performance. Many have preyed upon their students, particularly lower income and minority students, with well-documented records of low program quality along with low graduation and job placement rates. Many for-profits have also frequently engaged in deceptive practices that mislead students on each of those points.

As noted above, the Urban Institute’s review of existing studies and data confirmed the poorer performance of for-profits. Another study proponents of excluding for-profits cite was published in the Journal of Human Resources. It found certificate seeking students at for-profit institutions are 1.5% less likely to be employed and have 11% lower earnings if they complete the program than students in similar programs at public institutions like community colleges. This study also found the students enrolled in for-profit colleges earn less pre-enrollment than the median public institution student. Additionally, the median cost of tuition at for-profit institutions was found to be significantly higher compared to public ones. The modest gains in earnings among for-profit certificate students, according to the study, were often not enough to justify the debt they incurred to enroll. While graduation rates at for-profits are higher, for-profit’s opponents say the impacts on students after graduation confirm they do not provide the benefits public certificate-granting institutions do.

Economic choice between For-profit and Public Institutions

Supporters of the for-profit exclusion also argue the accessibility advantages for-profits claim over public and private non-profit colleges in the world of four-year college degrees don’t hold when it comes to shorter CCL programs. The public institutions that are by far the most active in career development are community colleges. An estimated 3.7 million community college students are enrolled in non-academic-credit programs. Supporters argue community colleges are generally as easy to get into and provide schedules that are as feasible for part- and full-time workers as for-profit programs. Supporters of the for-profit exclusion further argue community colleges are both much less expensive, as the Journal of Human Resources study found, and have a better track record for quality.

Proponents also argue we can’t rely on the other quality requirements discussed below to screen out the poor performing for-profits. They argue that, with a profit motive driving them, these organizations have proven to be too agile and creative in getting around such provisions in the past.

Some proponents of the for-profit exclusion agree it may make sense at some point to make them eligible if they can meet other quality assurance measures. Still, supporters argue it’s smarter to start Short-Term Pell with the institutions like community colleges with the best track record. They suggest it may then make sense to experiment with including for profits once experience is gained with the other quality requirements established.

Case Against

Opponents argue simply excluding all for-profits, including those with better track records, is counter-productive and unfair. They argue it’s better to protect against poor quality by establishing the quality requirements discussed below that all programs—for-profits and community colleges alike—must meet. Opponents reason that, if a for-profit career development program can meet the same quality criteria a community college can meet, then the interests of both quality and access are served.

Opponents also suggest the evidence does not consistently confirm community colleges are superior in all respects to for-profits. For example, they observe that the U.S. Department of Education documents a substantially higher graduation rate for students enrolled in shorter certificate and/or two-year associate degree programs at for-profit institutions (61%) than at community colleges (29%).

2. Excluding Totally Online Programs

The Jobs to Compete Act aims to ensure quality in part by excluding totally online programs from Short-Term Pell eligibility. The JOBS Act and the PELL Act both allow totally online programs that meet their other quality requirements.

Case For

Supporters of prohibiting exclusively online programs argue these programs are particularly prone to being poorer in quality. For example, they cite the study on for-profit performance published in the Journal of Human Resources. That study found earnings and employment outcomes were even poorer for students enrolled in for-profit certificate programs if the majority of the program was online.

Proponents of the totally online exclusion also argue the direct hands-on training critical for many workforce education programs cannot be effectively delivered online. For example, they suggest it’s impossible for a student in a program to become a plumber, electrician, or welder to get the needed hands-on training online.

Case Against

Opponents argue online programs are among the most cost-effective for students. Often by paying only $1,000 – $5,000, a student in an online program can obtain a credential that will get them a higher-paying job. They argue an additional accessibility advantage is that the online program schedules are more flexible. Much of the work can be done at a time and place convenient to the student and doesn’t require the added time commitment of commuting. They argue these considerations make the access tradeoff that comes with eliminating totally online programs especially stark.

Opponents suggest that the fact that some types of programs aren’t appropriate for 100% online training doesn’t mean that all online programs should be prohibited. In fact, fully online programs may be quite appropriate for programs in growing fields like cybersecurity, IT, finance, and software development whose core skill sets involve high levels of computer and technological fluency. The other approaches to quality assurance, they suggest, should be able to screen out programs that can’t be done effectively online.

3. Rigorous Administrative Approval Process

Another approach to assuring Pell Grants only support quality CCL programs is through a rigorous administrative process by which they would become eligible. All three major pieces of Short-Term Pell legislation already introduced require at least two administrative boxes for quality be checked:

- Accredited—Only providers who have been appropriately accredited to provide the workforce development programs they offer would be eligible

- Meets In-Demand Industry Requirements—A program must provide training that meets the hiring requirements for employers in in-demand industries

Beyond that, differences remain on what, if any, additional administrative approval criteria should be included. Below is a list of some of the most important ones that have been proposed.

Additional Administrative Criteria

- Leads to a Federally Recognized Postsecondary Credential—The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) provides federal definitions of credentials for various industries and occupations. This proposal would require a program meet these definitions so that graduates obtain a credential that will be recognized throughout the country.

- On State and Local Eligible Training Provider List (ETPL)—While there is wide agreement that Pell eligible programs must meet the hiring requirements for employers in in-demand industries, there are a range of proposals for how rigorous the administrative process should be to verify this. One proposal would require the entity who provides a skills education program be on a state’s and local area’s ETPL which must be maintained under WIOA. To get on the list, a program must first go through a formal process with the workforce board for the state in which it is offered. Then, it must also be approved by the local workforce board. The primary criteria by which state and local workforce boards are supposed to determine whether to include a program on the ETPL is whether there are sufficient high-skill, high-wage jobs available in that state or local area to justify the program.

- Administrative Determination that Provides Training in “high-skill, high-wage, or in-demand industry sectors or occupations” found in the State or Local Area—This proposal would require an additional administrative determination to the ETPL requirement above that programs provide skills for high-skill, high-wage, or in-demand jobs found in that state or local area. The House’s Jobs to Compete Act would require this determination to be made by the accrediting agency, while the Senate’s JOBS Act would require the determination be made by an industry or sector partnership.

- Meets Applicable State Requirements for Professional Licensure—Each state establishes criteria that must be met to obtain a license required to be legally employed in many occupations. This proposal would require a career development program fulfill a state’s applicable educational requirements for professional licensure.

- No Administrative Adverse Action in Past Five Years—This provision would require a determination that the program hasn’t been found sufficiently inadequate. For example, a program would only qualify if it has not been suspended or terminated in the last five years by the federal government under provisions of the Higher Education Act, by the state, or by the relevant accreditation agency.

- Must Provide Counseling—This proposal would require programs to provide participants with career counseling to help them achieve their educational and occupational goals. Counseling would include providing information about the industries, occupations, and certificates for which it prepares students, and about sources of financial assistance.

- At Least Half of Tuition and Fees Go to Educational Spending—Some program providers in the past have spent more than half the money earned from tuition on items other than the direct costs of providing the education. In the case of for-profits, much of the revenue has often gone to providing a larger profit for owners. This proposal would ensure this doesn’t happen with Pell eligible programs.

Criteria 1-4 above are included in both the Senate’s JOBS Act and in the House’s Jobs to Compete Act. In part because the Jobs to Compete Act includes for-profits (while the JOBS Act prohibits them), its sponsors thought it important to add criteria 5-7 as well. The Jobs to Compete Act also includes direct performance indicators discussed below. The PELL Act does not include any of the seven criteria listed above, instead emphasizing the outcome performance requirements discussed below.

Case For

Supporters of the additional administrative quality criteria argue they each have a self-evident quality to them. Look at each measure, they suggest. Would we really want to pay federal taxpayer dollars to subject students to programs that couldn’t meet each of them, they ask. They observe that a Pell Grant will only cover a portion of the costs of the program. The students will be responsible for paying the rest. Advocates argue students’ interests are advanced by attempting to ensure they aren’t left paying for programs that don’t place them in higher paying jobs but do saddle them with debt.

Case Against

Opponents of the administrative criteria approach suggest that, while each of the proposed requirements may sound good in theory, the challenge comes in the practical implementation. They note each additional administrative criterion would require federal, state, local government, and/or accreditation agencies to develop new regulations, procedures, data collection, reports, and forms to comply with them. They suggest one should then imagine all the time and effort it would take from thousands of government and accreditation agency workers to execute the administrative processes once they’ve been put in place.

More importantly, opponents suggest, imagine program administrators and teachers who are already busy and stretched thin. First, they would need to complete all the steps to apply for their program. If successful, they would then need to continue to collect data and file reports to stay eligible. Opponents observe even some early Short-Term Pell supporters who helped craft the initial bills introduced several years ago now express concern over the number and complexity of criteria that have been added. They worry fewer programs are going to apply than we want if all or most of the additional criteria are adopted, well-intentioned as they may be.

Opponents also argue some of the criteria are redundant. For example, they suggest the requirement a program be on the ETPL (#2) and the requirement of an additional administrative determination that the program provides training for high-skill, high-wage jobs found in the area (#3) are duplicative.

Finally, opponents suggest this approach leads to a heavy administrative burden for institutions even though the input criteria are only indirect indicators that cannot guarantee quality outcomes for students. Better, they suggest, to directly measure the desired outcomes like graduation rates, job placement rates, and earnings increases.

4. Outcome Performance Measures

Another quality assurance approach is to require that qualifying programs achieve certain direct measures of performance. Each of the two House bills incorporate this outcomes approach. The Senate’s JOBS Act does not include direct performance indicators.

- Graduation and Placement Rates—Both House bills require 70% completion and 70% job placement rates.

- Earnings Requirements—Both House bills also require that programs demonstrate their graduates earn more money after the program, though each establishes different measures of increased earnings.

- The Forthcoming Gainful Employment Rule—A new regulation established by the Department of Education called the Gainful Employment rule will likely be in effect by the time any Workforce Pell legislation is passed and implemented. Under that new rule, post high school nondegree programs and all for-profit institutions eligible for federal financial aid (including Pell Grants and student loans) would be required to meet two earnings requirements. First, programs must show that graduates’ payments on loans taken out for the program are no more than 8% of annual earnings or 20% of their earnings that are above 150% of federal poverty level. Second, at least half of a program’s graduates must have higher earnings than the median earnings of 25–34-year-old high school students in their state. The earnings requirements described below in both the PELL and the Jobs to Compete Act would be in addition to this new Gainful Employment rule.

- Increasing Earnings by More than the Program Costs—The PELL Act establishes a requirement designed to be sure graduates’ earnings increase enough to justify what they paid to enroll in the program. Three years after finishing, students’ median earnings adjusted by region must exceed the 150% of federal poverty level for individuals and must do so by more than the program’s total published tuition and fees. The current 150% poverty threshold for individuals is $21,870. To illustrate, a program whose students earned a median income of over $31,870 per year three years after completing a program that cost $10,000 would be Pell eligible.

- Earning More than They Made Before—Instead of comparing increases in earnings to the cost of the program, the Jobs to Compete Act compares graduates’ earnings to what they made before the program. Within six months of finishing, a program’s students must show a median earnings increase of 20% compared to the median of what they were earning before. Additionally, within 18 months of finishing, completers’ median earnings must be more than the median earnings for 25–34-year-olds with only a high school diploma or the equivalent in the state in which the program is offered. Currently, the national median earnings for 25–34-year-olds with only a high school diploma working full time and year round is $39,700. To illustrate, a program would qualify whose students had a median income of $30,000 before entering, more than $36,000 six months after finishing, and more than $39,700 18 months after finishing (in a state whose 25-34-year old high school graduates median income was equal to the national median).

Case For

Supporters of performance measures argue they are the most direct and effective way to ensure the quality of eligible programs. They suggest if the main aim of career development programs is to get students into higher paying jobs, then successfully achieving those outcomes should be the main factor determining eligibility for Pell Grants.

Some advocates argue if a high percentage of students successfully complete a program and get placed in a job earning substantially more it shouldn’t matter if the program was offered by a for-profit institution, exclusively online, or if it was able to meet extensive administrative criteria for quality. Conversely, they suggest, it matters little if the program was not offered by a for-profit, was offered in-person, or was able to check all the administrative boxes if it still isn’t effective at placing people in higher paying jobs.

While acknowledging programs will have an increased burden to provide the relevant data with this requirement, some supporters argue the outcome requirement approach is less burdensome than the administrative criteria approach. It will be easier, they suggest, to demonstrate compliance with a few outcome measures than to jump through many administrative hoops.

Supporters of the PELL Act’s specific outcome approach argue the most relevant earnings requirement is that the increased pay is enough to justify what students pay for the program. They observe that this standard is especially important because skills education program costs can vary widely, from less than $5,000 to more than $15,000. Those who must pay more should be able to expect more in earnings, they suggest. These supporters also argue this earnings requirement is especially effective at excluding for-profit programs that are not only considerably more expensive than community colleges but also don’t increase earnings by as much.

PELL Act supporters also argue that the 150% of federal poverty threshold is important because of federal policy regarding repayment of federally supported student loans. Below that level, students are not expected to repay their loans. The more students’ incomes exceed that level, the more they’re required to pay. PELL Act supporters argue that it’s appropriate to expect that programs supported by Pell Grants can increase their graduates’ earnings by enough that they can be appropriately expected to start paying back their student loans.

Supporters of the Jobs to Compete Act’s particular outcome approach argue the most relevant earnings requirement is that there is a meaningful increase over what that person was making before. They suggest this approach is especially warranted because students’ prior earnings can vary from less than $10,000 per year to more than $50,000 per year. They argue that, if a student was only earning $10,000 per year before, and is earning $12,000 per year just six months after completing the program, that’s still a success even if they remain below the 150% of federal poverty threshold of $21,870.

Case Against

Opponents generally fall into one of two opposite camps—that the proposed outcome requirements are (1) too high or (2) they are too low. Those arguing they are too high first observe that the new Gainful Employment Rule will provide sufficient assurance of success in placing students in higher paying jobs. Adding further outcome requirements is overkill, they argue, that will limit accessibility too much. In fact, some suggest the additional earnings requirements are counter-productive because they will create an incentive to discriminate. They suggest programs are likely to conclude that the most disadvantaged students—including lower income, women, and people of color—will have the hardest time meeting the earnings requirements. The result may be that programs will admit few of those students because they believe these students will have difficulty meeting the earnings requirements.

Opponents who argue the outcome requirements are too high also observe that program graduates will get the benefits of higher earnings over the remainder of their entire career, not to mention the benefits to their employers and society. For example, some suggest three years is too short a period to expect a full return on the tuition and fees investment in the case of the PELL Act. In the case of the Jobs to Compete Act, they suggest six months is too short a time to expect a 20% increase over what they were earning before entering the program. These opponents suggest the Gainful Employment rule is more than sufficient. If additional earnings increases beyond that are required, they suggest, the amount by which earnings must increase should be lower, or the time for achieving those gains should be longer, or both.

Opponents who believe the earnings requirements are too high frequently point to recent research conducted by the Urban Institute which found that only 21% of workforce programs overall would meet the PELL Act’s outcome requirements. For-profit career development courses fared even more poorly than the overall figures, with only 8% meeting the earnings requirements. Workforce development programs offered by public institutions, mostly community colleges, fared better with 81% meeting the PELL Act’s earnings requirement.

Although the study did not examine the more recently introduced Jobs to Compete Act, many argue even fewer would qualify under its earnings requirements. With the short six-month window by which graduates would need to show a 20% increase in their earnings, along with the requirement that within 18 months they earn more than median earnings for 25–34-year-old high school graduates, they contend even fewer than 21% of programs would qualify.

Finally, those who argue the proposed outcome requirements are too stringent also note that similar requirements are not made of college degrees eligible for Pell Grants. It’s unfair, they suggest, to require job placement and earnings increases of career development programs that many majors at many four-year colleges couldn’t meet though they are Pell eligible.

Other opponents argue the proposed performance requirements are too low. If the educational program is geared specifically toward quickly placing people in higher paying jobs, they reason, then they should be able to demonstrate the ability to do that to be Pell eligible. They reason that the biggest earnings boost should come right after gaining the new skills and qualification. For example, some argue programs should be able to demonstrate more than just barely meeting the PELL Act requirement that, within three years, earnings be more than 150% of the federal poverty level by the amount the program costs. Similarly, some argue the Jobs to Compete Act’s requirement of a 20% increase in earnings six months after completing a program isn’t enough to justify paying $15,000 or $20,000 for a program. They argue this is especially true if the graduates are only earning, for example, $4,000 more per year (if they were making $20,000 before the program and $24,000 within six months of completion, they would still meet the 20% increase requirement). Opponents to this earnings requirement also note examples like the one above make it clear the requirement is too low when one considers the student may in fact be worse off financially because many would now be carrying close to $15,000 or $20,000 of student loan debt.

There are also those who support performance measures generally but oppose other specifics in the two proposed approaches. Some like the increasing-earnings-more-than-it-costs approach in the PELL Act but argue the inclusion of the 150% of the federal poverty level (currently $21,870) is an inappropriate floor given there is such variation in how much participants were making prior to the program.

Some critics of the earning-more-than-before approach in the Jobs to Compete Act argue establishing the same percentage increase in earnings requirement regardless of how much the program costs doesn’t make sense. A person who completes a $20,000 CCL program should see a higher percentage increase in earnings than one who completes a $5,000 program, especially since they will likely have more in student loans to repay.

5. Assuring Future Career Options

Both the Senate JOBS Act and the House Jobs to Compete Act aim to ensure completing a workforce education program also boosts future opportunities beyond that program. The bills do this by requiring that programs eligible for Short-Term Pell have mechanisms through which completion leads to credits that can be applied to a future program in which the participant might enroll to earn a certificate or degree in a related field or vocation. The House PELL Act does not have such a requirement.

Case For

Supporters argue it’s important Workforce Pell doesn’t take us toward features of the European model that are at odds with the American dream. These advocates suggest the time and money individuals invest in workforce programs should also open to them possibilities for future upgrades in their career.

Case Against

Opponents argue that, while improved career opportunities in the future are a plus, earning credits for other related programs or degrees should not be required. They suggest that, if a program meets the other quality requirements, this additional requirement would limit accessibility more than the benefits warrant.

Thank you for taking the time to share your views on Career-Connected Learning!

Having reviewed the full brief, we now invite you to step back to reflect on the topic overall and answer the final questions below.

You’re free to navigate back to earlier sections to change your answers.

Members of Congress have specifically requested that we ask several of the questions below because they concern specific points under particularly active consideration. They’re eager to hear your answers as they work to find the right solution.

We look forward to sharing your views with Congress!